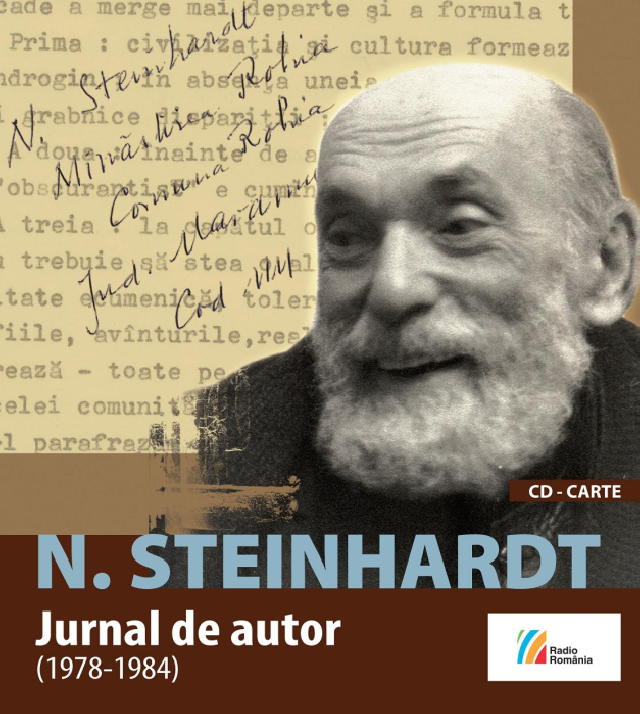

Nicolae Steinhardt

Nicolae Steinhardt was a part of a generation of Romanian intellectuals of the 20th century who clashed violently with history

Steliu Lambru, 24.06.2022, 03:33

Nicolae Steinhardt was a part of a generation of Romanian intellectuals of the 20th century who clashed violently with history. He was born in 1912, near Bucharest, and died in March 1989, nine months before the communist regime fell, aged 77. He was born into a Jewish family. His father, an architect and engineer, had fought in WWI, getting wounded and earning a decoration. He debuted in the magazine of the Spiru Haret High School magazine, and during his university studies he was a constant presence at the meetings of the literary circle called Sburatorul, led by the prestigious literary critic Eugen Lovinescu. He became a lawyer, and got his PhD in constitutional law from the University of Bucharest.

Steinhardt started writing literary criticism and essays under the pen name Antistihus. Up until he was kicked out of the Royal Foundation Magazine, under the anti-Semitic legislation passed widely in the late ’30s, he published three volumes of reflections on Judaic spirituality.

However, the new regime installed on March 6, 1945, would be one unfriendly to Steinhard, and to those who chose not to collaborate. A double whammy followed in 1947: he was fired once again from the editing room of the Royal Foundation Magazine, and was disbarred. In 1958, two years after the anti-communist revolution in Hungary, Nicolae Steinhardt was once again arrested, as part of the so-called Noica- Pillat group, named after philosopher Constantin Noica and writer Dinu Pillat. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison under the standard charge that the communist regime filed against its opponents: conspiring against social order.

In prison, he converted to Christianity and got baptized. He was released in 1964, after a stint of six years. His experience of incarceration is written down in his best known book, The Diary of Happiness, a book that had a very strong impact on the Romanian collective awareness in the 1990s. George Ardelean, who edited Nicolae Steinhardt’s correspondence, recalls the two types of inferno described in The Diary of Happiness, mentioned in some of the critic’s letters:

“There is the inferno of the detainee alone in a cell, a man in tough contact with the pure time he has to fill. Let us think, for instance, of Lena Constante, who was kept by herself in a cell for 3,000 days, meaning 8 years. It was a cell with only 4 walls, a bunk that was raised during the day, a toilet, with no access to phones, the press, books, with no clock or any other people. Then there was the other kind of inferno, that of the din, the noise. It was the din of an overcrowded cell. It reminds me of the paragraphs entitled Bughi Mambo Rag in The Diary of Happiness, where he wrote down the intersecting dialogues within the close space of a prison cell.

After his release, he published five volumes of criticism and essays, and after 1989, five more books of his were published, posthumously. After 1967, he starts to look for a monastery to retreat to and take the habit, and in 1980 he is received as a monk at Rohia Monastary, in Maramures.

“In The Diary of Happiness we have several sequences in 1938, when Steinhardt was in Switzerland, at Interlaken, attending a meeting of the Oxford Group, a Protestant ecumenical group. This is a major step for Steinhard closer to Christianity, after he failed to integrate at the synagogue. Between 1935 and 1937, together with his friend Emanuel Neuman, referred to as Manole in the diary, he tried to reintegrate at the synagogue, meaning taking on a fully Judaic identity. Their attempts failed, the diary doesn’t make clear why, and then the spiritual paths of the two friends split apart. So he was in Interlaken, he was fascinated by the discussions, he feels drawn in. One morning, an Irishman approached him, telling him that he had a dream that Steinhardt would get baptized. This episode also transpires in his correspondence.

Nicolae Steinhardt’s correspondence is fascinating, as editor George Ardeleanu confessed, and raises many challenges:

“There were a lot of challenges. First of all, just collecting the approximately 1,200 letters and identifying their recipients. The letters were gathered from the personal archives of the recipients, and from various institutions, such as the monasteries of Rohia, Cernica, and Sambata, the National Museum of Romanian Literature, and the National Council for the Study of Securitate Archives. Last but not least, there were the letters that were published after 1990 in various volumes and the culture press. The other extremely difficult step was to find a criterion to classify them, how to put in order these 1,200 letter? We had three possibilities. The first would have been grouping them by recipient, or ordering the groups alphabetically. The third criterion, which is the one we chose, was to combine the previous two: grouping the letters by recipient, and then ordering the letters chronologically for each of those.

The two volumes containing Nicolae Steinhardt’s correspondence sketch the grand work of a great thinker. They can also be read as volumes sketching the contemporary history of Romania.