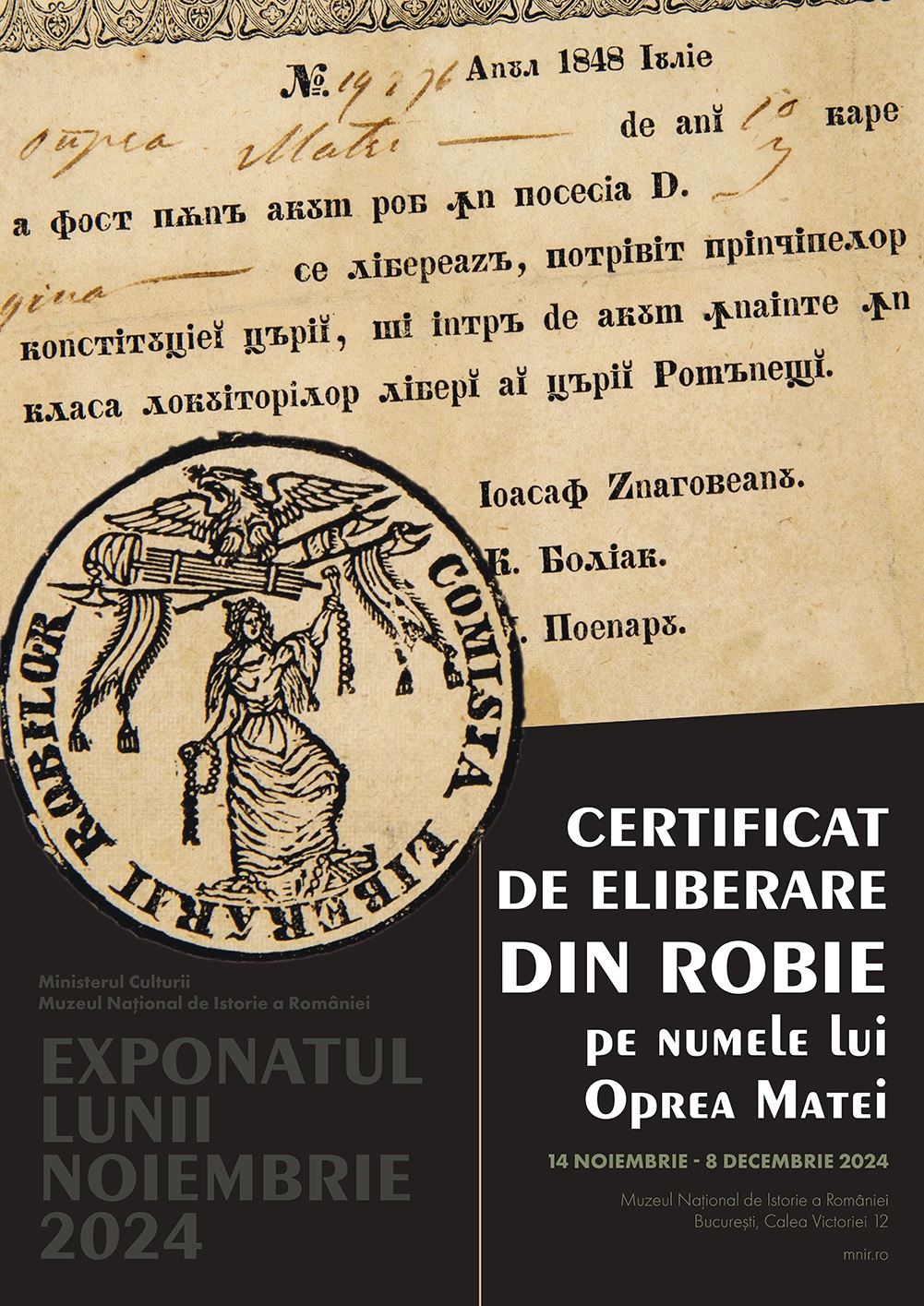

“Certificate of freedom for Oprea Matei”

The collection of the National Museum of History of Romania in Bucharest contains documents about the freedom of the Roma from enslavement dating from mid 19th century.

Ion Puican, 12.01.2025, 14:00

The Romanian Revolution of 1848 was part of the revolutionary wave that swept across Europe that year and an expression of the affirmation of the Romanian nation state and national identity. Bondage was common in the Romanian Principalities, a form of servitude that has similarities, as well as differences, with serfdom and slavery. It was mainly the people of Roma ethnicity who were subject to enslavement. They were the property of the master, who treated them like any other form of property, and who was to be compensated for if deprived of his property. The Penal Code of 1818 in Wallachia stated that “All Gypsies are born slaves” and that “Gypsies without owner are the property of the state”. There is little information, however, about the origin of the enslavement of the Roma in the Romanian Principalities.

The collection of the National Museum of History of Romania in Bucharest contains documents about the freedom of Roma from enslavement. One such important document is a certificate of freedom for Matei Oprea. Curator Andreea Ștefan tells us more about its significance in the historical context of that era:

“The certificate of freedom for Matei Oprea found in the collection of the National Museum of History of Romania speaks to an episode that forms part of a longer historical process in the Romanian Principalities, namely Wallachia and Moldavia, in the 19th century, between its 4th and 5th decade. I’m referring to the reforms that led to the freedom of the Roma slaves. The enslavement of the Roma population in the two principalities was the most important and the most acute social problem the two principalities had to tackle in the middle of the 19th century.”

Andreea Ștefan tells us about the revolutionary spirit of 1848, influenced by the European politics and culture of the time, quoting the passage about emancipation from the platform adopted in June 1848 by the revolutionary movement in Wallachia, the Islaz Proclamation:

“The liberation of slaves already appears in the document through which they make their platform known, namely the Islaz Proclamation, made public on June 21. The formulation reflects the deep shame that these young intellectuals, educated in the West, the heirs of Enlightenment values, feel at the idea that such an outdated and, above all, completely inhuman social practice is being perpetuated in their country. I quote, therefore, a passage from the text of the Islaz Proclamation: ‘The Romanian people reject the inhumanity and shame of keeping slaves, and declare the freedom of the privately owned Gypsies.’”

Andreea Ștefan gives us more details about both the attitude and the approach of the revolutionaries of 1848, as well as their responsibility at that time, namely the responsibilities of the Slave Liberation Commission:

“However, we must take into account, on the one hand, the pressure that was hanging over them, and the need to appear as acceptable as possible in the eyes of the population, therefore moderate. On the other hand, we must remember that these young people educated in France all came from the social elite, a social elite which often owned land estates, who earned significant income from the exploitation of the free labor provided by slaves. Just 5 days after the Proclamation of Islaz, on June 26, the body through which this important social reform was to be implemented was created, namely the Slave Liberation Commission. It had two main tasks: to issue freedom certificates and compensation certificates.”

Andreea Ștefan gives us more details about the Certificate of Freedom for Oprea Matei found in the collection of the National Museum of History of Romania:

“It is a standard form, printed in the transitional alphabet, that is, written in a mixture of Cyrillic letters and Latin letters, and is numbered 19276. Matei Oprea was 10 years old when he received the certificate, and had been in the possession of Ion Ghica. Ion Ghica was also a participant in the Revolution of 1848, and a militant for the liberation of slaves.”

Andreea Ștefan gives us an overview of the moment of 1848 from the perspective of liberation from slavery on the territory of the Romanian Principalities:

“The 1848 moment is a step back in the process of emancipation of the Roma. The legislation voted by the provisional government is ephemeral, ceasing its validity the moment the government itself ceases its activity.”

Finally, Andreea Ștefan shares with us some opinions about the effects of those legislative norms from 1848 to the present day:

“The way in which slavery affected the Roma community is extremely complex, profound, with short-term effects, which were felt immediately after liberation, but it also had long-term effects, which we certainly felt during the very tense moment of World War II, during the Holocaust of the Roma community, and which are felt in the tendency to marginalize the Roma community, still present in the community today.”