Dress fashion in church paintings

New book by historian Tudor Dinu looks at dress fashion in the Romanian principalities in early 19th century.

Christine Leșcu, 02.07.2023, 14:00

The Romanian principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia were under Ottoman sovereignty for over 100 years, from the start of the 18th century until 1877, and were therefore also influenced by Ottoman culture and civilisation. This influence was most visible during the Phanariote rule that began in 1714 in Moldavia and in 1716 in Wallachia and ended in both countries in 1812. During this time, the two principalities were ran by rulers chosen by the Ottoman Porte from among the Greek families from the Istanbul district of Phanar.

The “Orientalisation” introduced by the Phanariote rulers began to weaken, however, around 1806-1812 when, as a result of the Russo-Turkish war, the already westernised Moscow troops occupied the Romanian principalities. The salwars, both womens and mens, were replaced by dresses and trousers, respectively, the robes were replaced by riding coats and headscarves by hats. The adoption of the western fashion did not go unchallenged, and was not a smooth process, being interrupted by the political and military upheavals at the start of the 19th century that saw the Romanian principalities vacillate between Russia and Austria and the Ottoman Empire, the latter retaining its sovereignty over these parts for a long time. The decisive moment came, however, with the signing of the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829. From that point onwards, the oriental lifestyle would gradually but irreversibly be replaced by the western lifestyle.

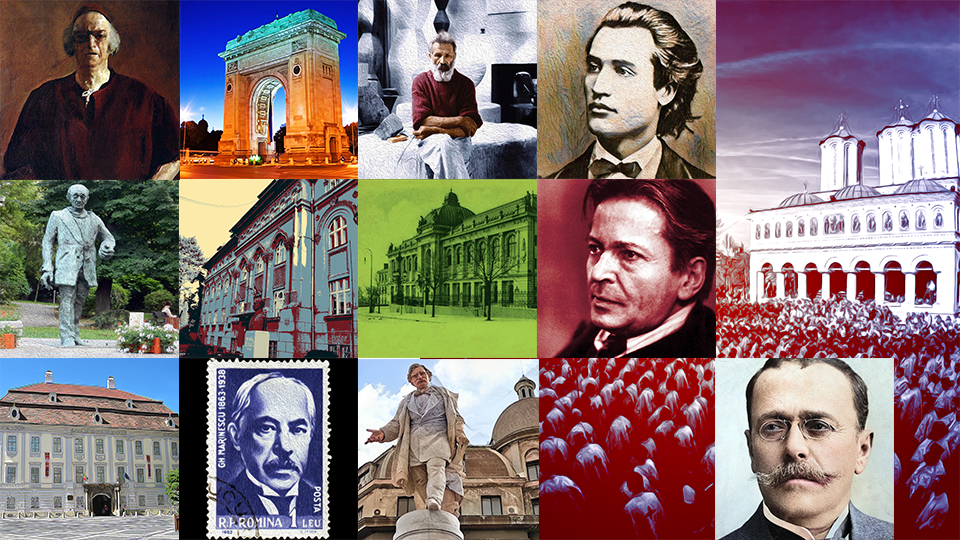

Fashion was the first to embrace the new, something that can clearly be seen in the portraits of the aristocracy dating from this period. This was true not only of secular portraits, but also the so-called “votive frescos” found in churches. Those dating from the early 19th century show that many boyars, especially from the countryside, were faithful for a long time to the old dress code and Oriental fashion. However, the founders portraits found in churches also depict boyars who had embraced the western fashion. Usually depicted alongside their families, they are a testament of how the new and the old co-existed in the way they dressed at a time of changes and eclecticism.

We asked historian Tudor Dinu, who has researched the founders church paintings made during this time, to tell us his conclusions:

“I studied 141 founders church paintings dating from this period and they depict more than 1,100 figures dressed in the fashion of the day. Traditionalist boyars continued to wear robes and fur caps, while their young sons replaced these items with riding coats and top hats. Around 200 outfits dating from the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century can be found in the collections of Romanian museums, as well as around 200 easel portraits. I have identified 1,100 figures of church founders dressed either after the Turkish fashion or what they used to call the German fashion, by German meaning western. The discovery of this as yet unexplored source has a significant contribution to our understanding of the fashion of the day.”

In his book entitled “Fashion in Wallachia. Between Phanar, Vienna and Paris. 1800-1850” (Moda în Țara Românească. Între Fanar, Viena și Paris. 1800 și 1850), Tudor Dinu has focused mainly on village churches founded by boyars in the first part of the 19th century in todays Gorj and Vâlcea counties, an area that was relatively prosperous at that time and more shielded from wars. The portraits in these churches indicate a continuation of dress traditions at a time of profound changes, as well as the transition to the new fashion, a transition marked by the co-existence of old and new elements. Historian Tudur Dinu explains this eclecticism:

“Important boyars who also had titles or were members of the princely council and held state positions could not afford to give up, at least not in an official or semi-official setting, the oriental dress, which was a symbol of their social status. Even the headdress reflected their positions. The ruler, for example, would wear a fur cap called ishlik with a white top. High-ranking boyars would wear caps with red tops and lower-ranked boyars caps with green tops. While waiting to be appointed, boyars and their sons would wear a form of head covering called kalpak, which looked like a balloon or a pear. They couldnt therefore stop wearing these outfits except in unofficial settings, at least not until the 1830s. The women, however, appear to have adopted the new fashion with extraordinary ease. As soon as the Russians occupied these parts, the ladies began to imitate the fashion brought over by the Russians.”

Those who had embraced the renewal of fashion did not shy away from being depicted on the walls of the churches they founded in their new “German”, that is western dress. This is the case of the founders of the church in Hurezani village, in Gorj county, where all family members look as if they came straight out of a fashion magazine of the day. However, the new fashion was also fiercely opposed by some. Historian Tudor Dinu explains:

“Their argument had more to do with religious conservatism. They believed the new fashion encouraged both women and men to sin. Trousers were the subject of heated debates between the traditionalists and the progressives, especially as it wasnt exactly comfortable for men to replace the old type of dressing. The enteri, which was a kind of unisex robe, was comfortable for all body shapes, while fitting into the newly adopted trousers would require sacrifices. The same with the riding coast. It was equally uncomfortable for the ladies, because of the corsettes, which were supposed to highlight their wasp waists.”

The new fashion did prevail in the end, its adoption being soon followed by a change in furniture design, interior design and architecture.