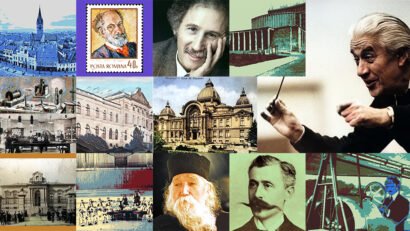

Scholar Ion Heliade Radulescu

Ion Heliade Radulescu is considered one of the founding fathers of Romanian modern culture

Christine Leșcu, 14.01.2017, 12:00

Ion Heliade Radulescu was born on January 6, 1802 in the southern Romanian town of Targoviste. A statue was erected in his honour, just across the University of Bucharest, located at the heart of Romania’s capital city. This is where statues of other icons of Romanian culture, such as Gheorghe Lazăr, Spiru Haret or Michael the Brave are located.

The poem Flying Dragon or the short fiction Mister Dragan, Ion Heliade Radulescu’s best-known works, have for long been included in mainstream textbooks. Ion Heliade Radulescu’s name is usually associated with the emergence of the first magazine in the Romanian language, The Romanian Courier, issued in 1829, with Heliade Radulescu himself as editor-in-chief.

Literary historian Mircea Anghelescu, asks himself just how well known a Romanian 19th century intellectual is today, an intellectual who in the early 19th century was socially and politically committed to the transformation of a country that was going through a difficult time. And to what extent Heliade Radulescu’s literary work stood the test of time? Mircea Anghelescu offers an answer to these questions, in a recording from Radio Romania’s Tape Archive: “Ion Heliade Radulescu is first of all a reformer of the orthographic system, and, broadly speaking, the father of modern education in the Romanian language. This self-made teacher, with little schooling and who, although not a philologist, had the genius of language, being also a practical man, introduced a key principle in his 1828 Grammar and in classroom teaching, a principle that remains valid to this day – one sound, one letter. He organized and structured grammar, at once compiling the core technical vocabulary of the discipline, without which grammar could not rise to the status of a curricular subject. He never ceased to plead, even during the years when his style was more Italian-like, for the need to take old religious texts as a language model. These very simple principles lay at the foundation of teaching Romanian in schools, to this day.”

Influenced by the French poet Lamartine, whom he translated, Ion Heliade Radulescu drew out the main themes of Romanian narrative and lyrical literature that had subsequently been developed by poets such as Eminescu. Also, Heliade-Radulescu was one of the first modern prose writers in Romanian literature, shaping up a typology of characters that were to be used by other generation of writers as well. As a journalist, Heliade Radulescu launched the polemical and satirical bite that had subsequently proliferated in Romanian journalist writing. And it was also Heliade Radulescu who, in 1837, after The Romanian Courier, launched a supplement with a feminist orientation titled The Courier of the Two Sexes.

Literary historian Mircea Anghelescu: ”His tremendous polemical appetite, the density of his critical discourse taking the shape of an outlook which is at once to-the-point and personal, his violent sarcasm, whose passionate charge was processed through the filter of a remarkable literary culture, all that make Heliade’s prose an area of resistance not only in the sphere of political and cultural journalism, that is journalist writing in its own right, where his contribution is less well-known, but also in the sphere of literature proper, that of satirical typology.”

In the pages Heliade Radulescu wrote when he was old, we can trace the first philosophical constructions in Romanian cultural sphere.

Mircea Anghelescu: “It was for good reason that Mircea Eliade included him among personalities such as Cantemir, Hasdeu, Eminescu, multifaceted personalities who could not separate the detail from the whole and who built, with the help of their own tools, the world capable to take in the thoughts they had not previously thought. Besides, Heliade Radulescu acted as a role model at a social level, without us realizing that. His words, that were later used as catch phrases, quite often taken out of context and distorted by his opponents’ misinterpretations, are still with us, with their implied reproach, since we were unable to make any sense of them and follow their example. His famous words, quite often ridiculed as an urge to an undertaking of indiscriminate writing, ‘Keep on writing, lads, just keep on writing!’ are actually an urge to tireless work, since they target writers and not others. Another very familiar quotation of his, ‘I hate tyranny, I dread anarchy’, is the expression of some sort of balance democratic societies have never ceased to seek, and whose absence has led to dramas we’re all too familiar with. Another catchphrase of his, ‘General gains to nobody’s detriment’, an allegedly demagogic formula, encodes the aspirations of any normally formed society, of a group whose interests are at the same time shared and divergent. Even the opportunism the Marxist historiography blamed him for, in fact his flexibility and his adaptation capacity, are nothing but a form of an often necessary compromise, without which the social and political life cannot exist.”