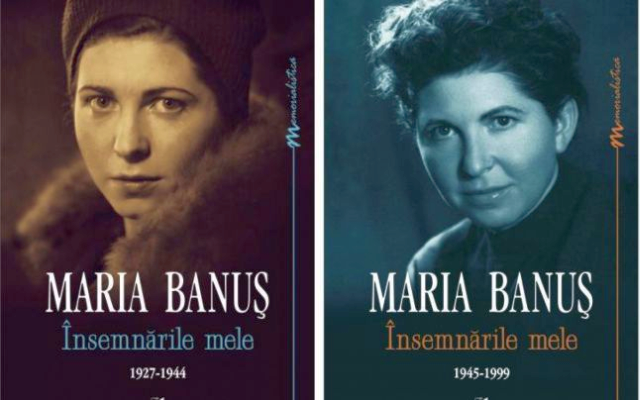

Poetess Maria Banus

April 10 marked 100 years from the birth of poetess Maria Banus, a politically controversial writer, but whose talent is appreciated by the public and critics alike.

România Internațional, 03.05.2014, 13:43

April 10 marked 100 years from the birth of poetess Maria Banus, a politically controversial writer, but whose talent is appreciated by the public and critics alike. Born in 1914 into a Jewish family in Bucharest, she made her debut in a major literary magazine run by poet Tudor Arghezi. Her first volume of poetry, the 1937 book ‘Girls’ Country’, revealed her as one of the most original writers of her generation. Unfortunately, when the communist regime was installed after the war, Maria Banus became one of the major voices of proletkultism, the official ideology extolling the achievements of the communist regime.

After 1965, however, she had a change of mind, and took a major turn in her lyrical register. The change proved beneficial, as in 1989 she was granted the Herder international award. The intense inner creative life of the poet, though controversial, is finally revealed to the reading public with the recent issue of her massive two volume diary ‘My Notes’. Covering 1927 to 1999, her diary is a fresco of the 20th century in Romania, according to writer Adriana Bittel:

Adriana Bittel: “Her confessional style of writing cuts deep, and does not shirk feelings and thoughts that are usually repressed, therefore the more shocking. The same ruthless treatment is applied to all, even the people she loves the most: her mother, the man she loves passionately, the kind and caring husband, her children and friends. The same sincerity is applied throughout her ideological route, which makes it easily understood, nuanced for whoever is inclined towards nuance, not for viscerally anti-communist people.

To this day, the name Maria Banus is associated unfairly with Stalinist and proletkultist lyrics. In fact, the books from the ‘50s, tailored for state propaganda, are only one stage in a very valuable writing career that starts in 1937 with ‘Girls’ Country’, continued three decades later with volumes in which she recovers her lyrical vein, nurtured from great modern poetry. By putting together fragments over seven decades, we compound a destiny with other destinies and history itself. It is a complete novel, erotic, political, a novel of marginalization and ethnic persecution, of the meanders of friendship, of disappointment and idealism of relations between parents and children, of suffering out of envy or vanity.

Also, at the end we find some heart- rending pages about the mental and physical suffering of advanced age, of decay and isolation. There is a biological aging and a social one, and the harder to bear for her is the social aging.

Literary historian Geo Serban, the writer’s editor, believes that these notes shed a surprising light on the poet that was marginalized by the regime she had trusted at its beginnings:

Geo Serban: “Her greatest suffering was that she compromised on her talent, and risked losing her streak of originality because of the circumstances. That is why her diary becomes a re-examination of the past, and an explanation as to what happened. She was not an opportunist who embraced a political cause thinking of the material advantages. She risked her life in 1941-42. She was putting up posters at night. She sheltered in her house for several months a high ranking communist party member who had been condemned to death, and was wanted by state security services. By doing that, she put her own life in danger, hers and her family’s. I was surprised by the intellectual tension of these notes. You don’t usually expect a poet to put reading before his own talent. She may have believed in talent or not, but she thought that her talent was dulled by the life she led, but she was extremely thirsty for culture.”

Maria Banus passed away in 1999, leaving behind two children, and a poetic opus that is worthy of a rereading.