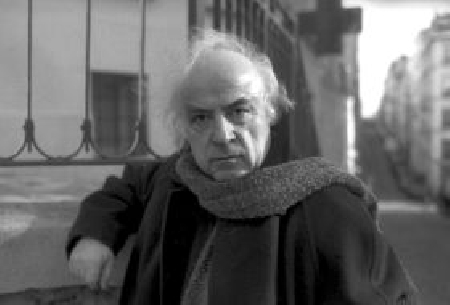

Writer Norman Manea

One of the best known Romanian writers abroad, Norman Manea was the special guest of the Iasi International Literature and Translation Festival.

Corina Sabău, 10.01.2015, 14:00

One of the most prestigious guests of the International Literature and Translation Festival in Iasi, held in October 2014, was writer Norman Manea, the author of many books, among which “The Black Envelope”, “About Clowns: the Dictator and the Artist”, “The Return of the Hooligan”, “Envelopes and Portraits”, “Compulsory Happiness”, “The Lair”, “Black Milk”. Norman Manea was born into a Jewish family and in 1986 he settled in the United States. He experienced exile and deportation at a very tender age. “My existential route has been rather complicated. I experienced the first exile at the age of five. In 1945 I was feeling as an old man of 9” said Norman Manea, a good friend of writer Philip Roth and poet Edward Hirsch, the latter one of his guests at the festival in Iasi.

The host of the evening was Romanian writer Carmen Musat, editor in chief of the Observator cultural magazine, who started from a statement by Oxford Lecturer Edward Kanterian, with whom Norman Manea carried an 11 year long dialogue, which was eventually published in the author series issued by Polirom publishers. Against that background, Edward Kanterian said that Norman Manea is the Romanian author that triggered three essential debates in Romanian culture. Carmen Musat:

“In 1982, in an interview to Familia magazine, Norman Manea annoyed the then officials, but also some of his fellow writers, as he dared talk about nationalism and the way in which obedient writers dealt with that issue. In 1992, he published in Revista 22, run at the time by Gabriela Adamesteanu, an essay tackling Mircea Eliade’s affinities with the legionnaire movement, thus breaking a taboo topic in Romanian culture and daring to discuss Eliade’s involvement in an unhappy ideology. Then in 1997, when Mihail Sebastian’s Journal came out, Norman Manea talked about incompatibilities, actually, quoting Sebastian, about the fact that there are no incompatibilities in Romanian culture. Norman Manea has always been fascinated with nuances, but he has never been afraid of displaying a trenchant attitude in relation to issues that we normally keep quiet about.”

Starting from these observations made by Norman Manea, Carmen Musat asked a question: why our relationship with memory gets tense when we put it in front of the mirror of truth? Norman Manea:

“I don’t see myself as either a polemist, or an instigator. I’ve just explained my personal opinions and a way of seeing literature in the history of a nation. I’ve talked about the difficult periods in Romania’s history, but I usually refuse to talk in collective terms about Romanians, Jews, etc. I am usually interested in the individual, in what an individual can and should do. I am also interested in the radical differences between human personalities. As for the memory…Cases of self-analysis are rather scarce in our history, just like the cases of critical analysis of errors. I would say that this comes from a certain kind of hedonism. The Romanian people, which I have always been part of, though some may not be too happy about it, is, in my opinion, a hedonistic people. The saying that we have not begotten saints, we have begotten poets, is a mark of this hedonism. Hedonism means enjoying what every day has to offer and the joys that life places at your disposal, it means more interest in art than in the sacred. That entails a certain kind of adjustment, to the immediate; and that may, in turn, lead to ignoring the past.”

Another question that Carmen Musat asked Norman Manea at the International Literature and Translation Festival in Iasi was about the role of intellectuals in the contemporary world, a post-totalitarian world, threatened by all sorts of crises. Norman Manea:

“I usually avoid proposing or imposing a role on somebody. There are intellectuals locked inside their existence as thinkers, there are intellectuals always mixing up with the crowds and fighting for an ideal. I believe that all these are personal options. I would like to believe, and I would be happy if that were so, that the intellectual could play a positive role in the national debate. Their role, their position, their mission have grown weaker in modern society, which is very practical, even mercantile, with money being the main criterion. Prestigious intellectuals, those who at some point were educators in society, have been in the shadow for some time now, and I don’t think they are likely to come out any time soon.”

Held under the auspices of the European Commission Representative Office in Romania, the International Literature and Translation Festival gathered over 300 professionals in the field, both from across the country and from abroad, writers, translator, editors, festival organisers, literary critics, librarians, book distributors, cultural managers and journalists.