Controversies around religious education in Romanian schools

Religious education, which is part of the national curriculum in Romania, has recently come under intense criticism.

România Internațional, 30.07.2014, 13:42

Taught in Romanian schools throughout the undergraduate years, religion as a school subject has come under criticism from both some of the parents and part of civil society, on grounds of the freedom of religious belief. There are parents who do not want their children to take religion classes because they belong to a different religion than that being taught in schools, or because they do not hold religious beliefs or simply because they think certain parts of the textbooks may have a negative impact on their children.

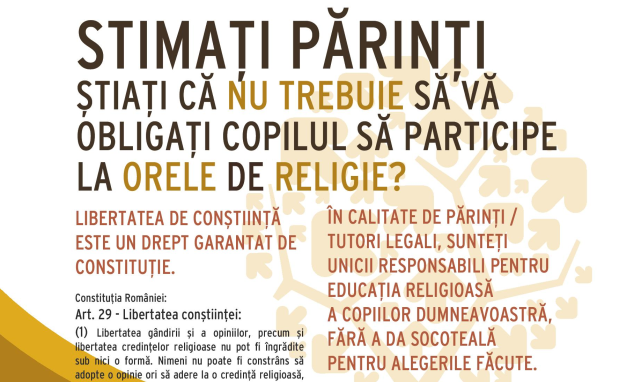

Many parents, however, are not sure whether the law allows them to withdraw their children from religious education lessons or how this can be done. The Romanian Secular-Humanist Association has launched a campaign to clarify these aspects. Romanian law allows parents to withdraw children from the religious education classes. But do schools provide an alternative? Can these children take other classes instead, or at least spend that hour in a supervised environment? Here is the executive manager of the association, Monica Belitoiu, with some answers to these questions:

“Many parents were surprised to find out that they may withdraw their children from religious education classes. Those who chose to do so were generally people who belonged to a different religion or who disagreed with how the subject was taught. At the start of every school year, we went to several schools and ran information campaigns about this particular law. Some school principals agree with us, others claim we don’t understand the law. There are also school principals who say they cannot allow children not to attend religion classes when they are scheduled in between other classes simply because there are no spare classrooms where these children can wait for their next class. Some parents have special arrangements with the school, and their children can spend this time either at the school library or in after-school.”

Meanwhile, teachers and representatives of school inspectorates have recognised children’s right not to take religious education classes, although under the education law this is not an optional subject. Mihaela Ghitiu teaches religious education at the Ion Neculce National College in Bucharest:

“Religious education is part of the compulsory subjects. What made people regard it as optional is the fact that children are allowed not to attend the classes if they belong to a different denomination. In such cases, they may attend other classes specific to their religion, where this is possible. The curriculum is specific to each denomination, there is a special curriculum for the Orthodox children, another for Catholics and so on. All these curricula are approved by the Education Ministry. If parents want their children not to study religion at all, they are free to do so, because the education law is in line with the Constitution, which guarantees the freedom of religious beliefs.”

Roman-Catholic or Muslim children in Romania may withdraw from the religious education classes if their school only provides classes for Orthodox children. They are free not to attend, but if they have no place to go they have to remain in the classroom. Religious education teacher Mihaela Ghitiu explains:

“I have a Muslim student in my class and when we discuss a topic that is related to his religion, he is welcome to contribute. He hasn’t withdrawn from the class. But I don’t grade him, of course.”

To avoid such situations, the Romanian Secular-Humanist Association suggests that religious education classes should not longer be scheduled in between other classes, but at the start or at the end of the school day. Children who do not take these classes would be able to come later or leave earlier from school, and the school would no longer be responsible for their supervision. Parent associations support this initiative. Here is Mihaela Guna, the president of the Federation of Parent Associations:

“I think this is the fair thing to do, because some parents don’t withdraw their children from religious education classes only because their children would be unsupervised for an hour. So they let them take the class just to make sure the children stay in school. I believe it would be normal for children who do not wish to attend religious education classes to be able to take an optional course instead.”

Instead of an optional class, the Secular-Humanist Association proposes the replacement of religion as a subject matter with the history of religions, which would teach children about the diversity of religious beliefs and denominations. Mihaela Guna supports this initiative because this would avoid teaching certain religious aspects which small children may find shocking:

“I think it would be much more interesting to teach them the history of religions or other things instead of, for example, the ritual of washing the dead. I think children should learn more about religion in general and less about dogmatism. There are many children who are afraid that if they do not say or do certain things, God will punish them. I think we should look at religion in a different way.”

Teacher Mihaela Ghitiu says some elements related to the history of religions are already being taught during religious education classes:

“Religion proposes values and develops virtues and teaches children how to live in a community. However, it’s impossible to talk about virtues without talking about their opposites, about sins. The Romanian Secular-Humanist Association believes children should not be taught about punishments, about hell or death. But in traditional families, when grandparents died, children were brought to their deathbed to be given their last blessing. It was part of life. Parents can talk to their children about these things, in a delicate way, as these are things that they themselves will have to face in their own families.”

The debate over religious education in Romanian schools has also reached Parliament, where a recent initiative provides for replacing religious class with ethic and civic culture classes.