Bucharest Under Occupation (1916-1918)

A look at the two years of German occupation in Bucharest at the end of WWI

Steliu Lambru, 09.01.2017, 13:08

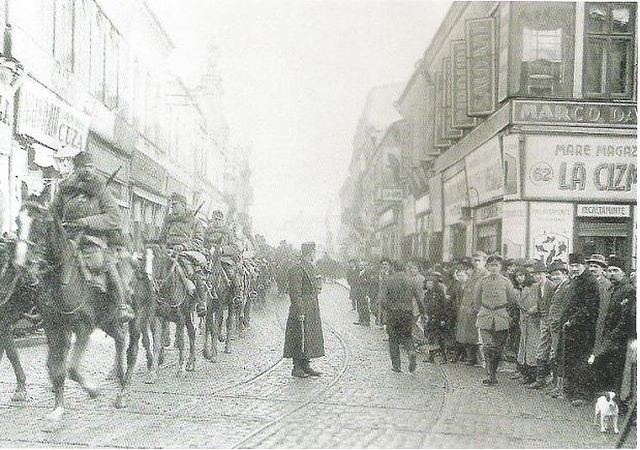

In December 1916, Bucharest was occupied by the Central Powers, with the government taking refuge in Iasi. The occupation regime was harsh, and Romania was treated as a defeated country. The treaty to seal the defeat was supposed to be signed in March 1918, but it was never ratified by King Ferdinand I. Fortunately, the occupation only lasted until November 1918, when WWI ended, leaving behind around 10 million dead. Together with Sorin Cristescu, historian with Spiru Haret University of Bucharest, we analyzed what the German occupation meant:

“They came in by a few columns. Mackensen rode a convertible, reaching the royal palace in Bucharest ahead of Austro-Hungarian troops, and the palace was offered to him as his residence. He did not use it as such, but moved in the Meitany house. The military regime in the country, to quote a chronicler of the times, Virgil Draghiceanu, lasted 707 days. There is even a book by that title, ‘707 Days Under the German Fist‘.

The occupation was tough. The conquerors took full advantage of the situation, as Sorin Cristescu told us:

“It was a premeditated plunder against the civilian population, which was robbed of everything from sugar to bed linen. Metal was lifted from all around Bucharest, to go into building guns. The occupation also brought traffic restrictions. They tried to exterminate stray dogs with guns. If we are to believe what politician Constantin Argentoianu wrote in his memoirs, all the prostitutes were rounded up and taken to an army barracks in Mizil. They were given medical tests and treated, all expenses paid by the state. The Germans also had admirers, among them Conservatives Alexandru Marghiloman and Petre P. Carp. Carp said ‘never have the streets of Bucharest been swept so clean. These Germans should stick around about 10 years, and make serious people out of us. However, it was plunder on a large scale, especially in agriculture and the oil industry, with destruction of oil rigs and equipment. Mackensen had 100,000 prisoners, and he sought out among them oil workers. They were given the right to stay in Romania, the rest were sent to Germany. This is how the oil industry was back on track within 6 months.

We asked Sorin Cristescu about the behavior of the other occupiers:

“The Bulgarians gained a sad notoriety for robbing Capsa, the famous confectioners, which had a collection of fine liqueurs, and robbing the Romanian Academy, where they attempted to steal manuscripts. The most important moment came in January 1917, when the Bulgarians stole the relics of St. Demetrius the New, patron saint of Bucharest. During that harsh winter, they put them in a car that broke down close to the Danube. Even if it had not broken down, Field Marshal Mackensen would have thwarted that robbery attempt. Art historian Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcas went to Mackensen, explained the situation, and Mackensen agreed for the Bulgarians to be immediately captured and have the relics returned. As for Turkish soldiers, they wanted the two cannons flanking Michael the Brave’s statue. These were two cannons captured at Plevna in 1877 by the Romanian army, which the Turkish army requisitioned. As regards the Austro-Hungarian armed forces, there were no particular problems to report.

The conquest of the south of Romania and Bucharest was a success for the Central Powers, taken as such by all who left written testimony.

VM TRACK: “When we read the memoirs, sometimes humorous, of the Germans who took part in the Romanian campaign, we find out it was referred to as the ‘fat rooster campaign’. That meant that they found huge quantities of food. The Germans went to restaurants and ordered everything on the menu. They paid, of course, and ate to their heart’s content. The problem was that those troops, considered second line, recovered so well in a few weeks that the doctors told them that they were fit for first line. And then people started claiming they had all sorts of illnesses. After the occupation, General von Morgen decided that each soldier had to send home every month 12 kilograms of food. As he wrote, ‘Woe be to the soldier who gets back from home leave with food in his satchel’. No one was allowed to get back from Germany carrying food, because during the war people were starving to death. If they had not taken over the south of Romania, the situation would have been truly dire. That is what they announced in Germany, that Romania had fallen, which was not true, because only two thirds had fallen to the enemy. People who had relatives in the army that occupied Romania were not worried, because there was no fighting there, and they got 12 kg of food every month. And suddenly, in the summer of 1917, the news came in like lighting: at least 10,000 German troops had fallen in battles in places with strange names like Marasti, Marasesti, and Oituz.

The occupation of Bucharest lasted close to two years, ending in November 1918, which resulted in the emergence of Greater Romania. (Translated by C. Cotoiu)