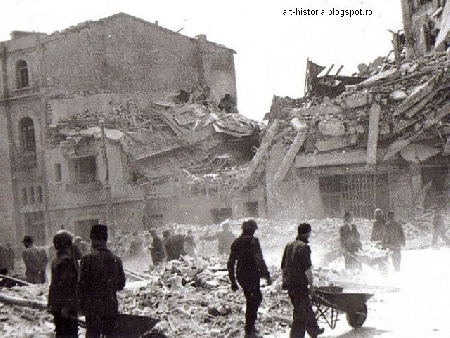

The American bombings of April 1944

On April 4th, 1944, a few hundred American bombers took off from Foggia, in Italy, to survey the Romanian air space and bomb targets of economic importance.

Steliu Lambru, 22.07.2013, 11:38

This was a US attempt to aid its Soviet ally in the struggle against the coalition led by Nazi Germany of which Romania was part at the time. However, the American raid also targeted Bucharest, where they were attempting to destroy the main railway station switches. This resulted in a few thousand innocent civilians getting killed, mostly refugees from northern Moldavia. Writer Mihail Sebastian wrote in his diary, in his entry of 8th April 1944:

“Yesterday afternoon I went to the neighbourhood of Grivita. From the railroad station to Basarab Boulevard, no house was left unscathed. The view was harrowing. They were still taking out the dead from under the rubble, three women were wailing, yanking their hair and rending their clothes, mourning a smouldering corpse freshly taken out of the rubble. It had rained in the morning, and the entire neighbourhood was smelling of mud, soot, burned wood. An atrocious, nightmarish view. I couldn’t get beyond Basarab, I went back home with a feeling of disgust, horror and powerlessness.”

The official toll was 2,942 dead and 2,126 wounded. The social memory was also deeply touched by these events. Conductor Emanuel Elenescu, talking for the Oral History Centre of public radio in 1994, recalls the feeling on April 4th, 1944.

Emanuel Elenescu: “A passive defence exercise had been scheduled a week before, for 10 o’clock. As the people were undisciplined, they couldn’t be bothered. The sirens went off to announce it was over, and people went about their business. Around 1:30 or 20 to 2, the alarm sirens went off again. People didn’t pay any heed, they thought it was the exercise. I was on Popa Tatu Street, close to the radio building, and I met my mother and brother, who were eating at a buffet close to Buzesti Square. After the sirens stopped, we heard airplane noise. Since I had a good musical ear, I realised that it wasn’t the usual, it was the noise of very heavy airplanes, it sent chills down your spine. It’s as if the sky was trembling. I said: “Mom, let’s get to a shelter, this is a real alarm!” We went into a grocery store on Grivita Boulevard, and the bombing started. There were three waves. The shelter was quaking, it felt like an earthquake. These were Liberators, Flying Fortresses, they had machine guns in the front and the rear, both. When we got out, Matache Market was full of dead people. A tram still standing was leaning against a house, and the rail was bent. All the dead people were untouched by the bombs, all died from the shock wave. They all had blood on their faces, they were bloated too. At the moment of the explosion, a vacuum forms, and people imploded.”

Public radio got relocated, and Emanuel Elenescu recalls how it continued its broadcasts as the American raids also went on.

Emanuel Elenescu: “In the evening I had a broadcast on the radio, I was playing with the orchestra. I went to the radio station, everything was down to the ground, there was nothing we could do. There were daily alarms, even though the bombing had stopped. Since we couldn’t broadcast, we got an order from Marshal Antonescu to disperse. We got dispersed to Bod, a village in southern Transylvania. It was a Saxon village, there were few Romanians, and the village was 2 km away from the emitter there. We put together a makeshift studio in a pub held by a Saxon by the name of Schuster. I had one, sometimes two broadcasts a day, live. It was still business as usual. Whenever we heard in German “Achtung, achtung!”, we knew the first waves of bombers were arriving. One day, I was conducting Tchaikovsky’s Pathetic Symphony, and I heard a sound like kettle drum. I looked at the drummer, he looked at me. It was the sound of American bombers flying at low altitude over Bod, right above the village, they were about to bomb Brasov. It was either a mistake or a lugubrious joke made by a sound engineer, who didn’t tell us that we were under alert. And everyone ran off into the fields.”

Professor Olimpiu Borzea, in 2001, spoke to the Oral History Centre as an eyewitness to events as well.

Olimpiu Borzea: “In April and May I went on a tour of hospitals around the country. I went to Socola, then Vaslui, and from there to Bucharest, to Elisabeta Hospital. After that I moved to the Franciscan Street, there was a Catholic school there and dorm room buildings. When they started dropping bombs, they took us to the basement, and you could hear the bombs. A soldier kept complaining, and I told him to shut up, I said: “What kind of a fighter are you, even these young girls, the nurses, don’t complain as much as you do.” He didn’t know how to use a thermometer, he used it at the wrong end. The poor nurse came and told him: “You have a fever, you’re burning up.” And put the thermometer back. I asked to see it, and saw it was broken. I gave him mine, and it turns out he didn’t have a fever at all.”

The American raids fell within the logic of the war, that of destroying or demoralising the enemy. However, it was the civilians who paid the highest price, even though they had no say in the conflict.