Civil Service in Early Romanian Modernity

In the first half of the 19th century, the modern Romanian state was taking shape against the background of major shifts in international relations.

Steliu Lambru, 01.04.2013, 12:48

31.03.2013

PRO MEMORIA –

Welcome to PM, we are XX and YY.

It was the time of the Napoleonic Wars, but also the early days of Romanticism. It was a time when the idea of nation was springing up, and small territories under the heel of the Ottoman and Russian empires saw it as a means to achieve emancipation, whether economical, social or political.

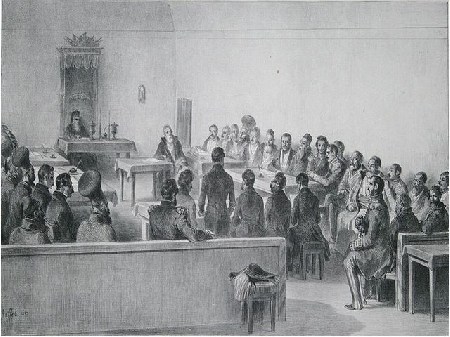

In the Romanian principalities, the first laws to reflect the new values were the Organic Regulations of 1831 and 1832, issued during the rule of Russian-appointed governor Pavel Kiseleff during the Russian protectorate. Its most forward-looking provisions had to do with political life: separation of powers, electing the ruler and the legislative assemblies, and the attributions of each institution. This was the foundation of bureaucracy and of civil service. Historian Constanta Vintila-Ghitulescu from the “Nicolae Iorga” Institute of History believes that the beginning of democratization of the Romanian space begins with the enactment of these Organic Regulations and the fact that they introduced merit-based appointment of public servants.

The ideas of national state and public participation in decision making were received with much enthusiasm by Romanians. However, reality many times did not match the theory. Historian Constanta Vintila-Ghitulescu told us more about the situation by mid-19th century, when tradition was still strong:

Constanta Vintila-Ghitulescu: “In early modernity, we can see how the leading families in society still held the monopoly over the most important positions in the state apparatus centered on the ruler. As for minor positions in chancelleries, what is significant is the fact that a bureaucracy was gradually forming, and the idea of being employed by the state as a civil servant became the dream of almost every Romanian. That is because this was the time when the idea of a pension emerged, and that of holding office over a period of time. After 8 years you had the right to a pension, and if you died, this would be inherited by the widow. You also had a uniform, and you received money for the clothes you had to wear at work. A civil service class emerged, which we can see reflected in Ion Ghica’s writings. In one of his letters, he complains that Romanians are avidly chasing these state positions, which started getting bloated, and that you could no longer find people with regular crafts, such as cobblers, tailors, people to do the small, indispensable jobs that everyone needs.”

The enthusiasm for emancipation was not able, at first, to overcome the mentalities shaped along centuries of past history. Constanta Vintila-Ghitulescu points at this as being one of the biggest challenges facing state reformers:

Constanta Vintila-Ghitulescu: “In early modernity, relations held a prominent place, and so did working for or being in the presence of important people. If you were part of the household of an important nobleman, such as Grigore Brancoveanu, if he took up an important state position, such as minister, his entire little flock of clientele moved into the department he was in charge of. If you had been a mere petty supervisor on a nobleman’s land holdings, you could become a chancellery scribe, provided you could write. Or you could be appointed head of police in a small village. If you didn’t have ‘props’, as Iordache Golescu put it, you could not penetrate the state system. The selection was clientele-based, and abuses were common. But don’t suppose people weren’t being punished. They would get fired for not doing their job, but then they would get taken back because they were under someone’s protection.”

The liberalization of public positions also brought about a change in terms of what aspirations people had for climbing the social ladder. This is when the nouveau riche emerged. Constanta Vintila-Ghitulescu defines for us this new social category:

Constanta Vintila-Ghitulescu: “In the early 19th century, the people of the grand nobility who did not manage to obtain the high positions in the state started feeling threatened by characters who manage to penetrate the entourage of the ruling prince and use the newly-found favour to penetrate the grand nobleman class. They marry the daughters of such nobles and gain land holdings. Afterwards they feel entitled to high positions in the state. These nouveaux riches were despised by the people of the old grand noble families. Iordache Golescu, whose writings are centered on the nouveaux riches, was a descendant of such an old Wallachian family. In the early 19th century, some princes bring into their entourage future ruling princes from Constantinople, Greek in origin, who take advantage of their relationship with the prince. They start buying land holdings and all of a sudden are given important and well-paid positions. They get rich overnight, and the old noble families, such as Brancoveanu, Golescu, Bals and Rosetti start feeling threatened, and started making up insulting names for this new class. Their characteristic was that of being stingy, avaricious, and of using any leverage they could get in order to reach the highest rung of the ladder possible.”

The birth of Romanian democracy in the early 19th century reflected a complicated blend of Western ideas of modernity, new institutions, local mentalities, and personal ambitions. The results were not always ideal, but they gave that period the special charm it holds for us today.