Braşov – 35 years on

Romania marks the 35th anniversary of the anticommunist uprising of the workers in Braşov.

Bogdan Matei, 15.11.2022, 13:50

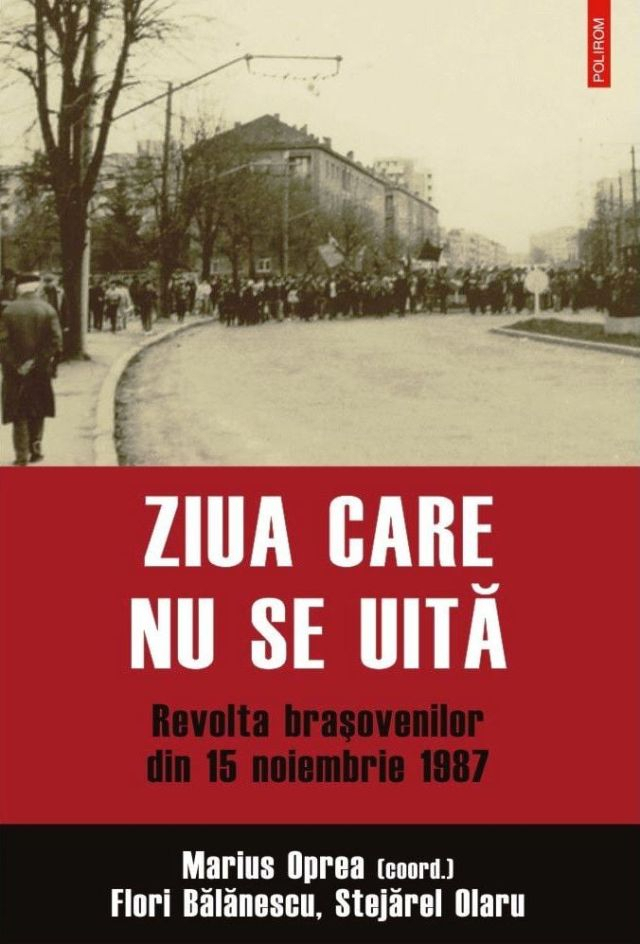

The

day we’ll never forget is how we can translate the book written

by two Romanian historians, Marius Oprea and Stejărel Olaru, about

the anticommunist uprising of the workers in the central city of

Braşov on

November 15th

1987. Although severely repressed, it did

shake

Nicolae Ceauşescu’s communist dictatorship and historians

say it was a prelude to the December revolution of 1989, which swept

away the almost 50-year-old regime imposed by the Soviet occupation

army at the end of WWII.

At

the

time, the last Soviet leader, the reformist president Mikhail

Gorbachev was

breaking away with the police state inherited from Lenin and Stalin

and was trying to humanise the system through glasnost,

transparency, and perestroika,

restructuring. In Poland, a satellite country of the USSR, like

Romania, the Solidarity workers’ union was staging protests and

marathon strikes, bringing to a standstill a regime that still

pretended to govern on behalf of and in the best interest of the

workers.

No

wonder that the explosion of anger of the workers in Braşov

occurred

on one of the biggest industrial sites in the socialist republic,

against the sinister backdrop of the late 1980s, when the

precariousness of living was doubled by police surveillance and the

cult of personality surrounding Nicolae Ceauşescu.

The

president of the 15th

November 1987 Braşov Association Marius Boieriu recalls:

We

demanded bread, which was rationed and which we could only get after

queuing for long hours after we finished our shifts. We demanded

heating for our cold apartments, where the children of my older

colleagues were shaking with cold. I was 20 years old at the time. We

demanded freedom. To have all these, we chanted ‘Down with

Ceauşescu!’ Hoping the people of Braşov would join us, we sang

the song ‘Wake up Romanians’ on our march towards the party’s

county headquarters. And two years later, the Romanians did wake up.

It’s hard to put into words what we went through.

The

workers who made their way into the local seat of government threw

Ceauşescu’s portraits and the red flags of the communist party out

of the windows. Later, some 300 protesters were arrested and

interrogated under torture by the Securitate, the state’s political

police. The regime chose to treat the protests as isolated cases

of hooliganism

and the penalties did not exceed three-year suspended sentences, a

relatively lenient penalty in the communist criminal code. It may

have also helped that a few days after the uprising, the students of

Braşov

installed a banner on campus on which was written: The detained

workers must not die, an indication that the discontent was shared

by the majority of Romanians. Two years later, a revolution put an

end to a regime which the Romanian post-communist state itself would

officially condemn as criminal and illegitimate. (CM)