Tradition and avant-garde in the art of modern Romania

“La Belle Époque was a period in French history, during the Third French Republic, characterized by regional peace and economic prosperity.

Monica Chiorpec, 01.06.2019, 14:00

“La Belle Époque” was a period in French history, during the Third French Republic, characterized by regional peace and economic prosperity, a peak of colonial empires and technological, scientific and cultural innovation. Romania was also sharing the European current of thought of this period from before WWI. The Exposition Universelle of 1900, better known in English as the 1900 Paris Exhibition, was a world fair held in Paris to celebrate the achievements of the past century and to accelerate development into the next. Paris was a place where geopolitics acquired cultural dimensions. Countries from around the world were invited by France to showcase their achievements and lifestyles. Later, the inter-war avant-garde would attempt to change the established art forms, and bring in new artistic elements.

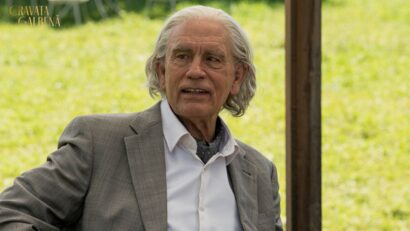

Art historian Erwin Kessler has participated in a series of debates entitled “Ideas in the Agora”, organised by the Museum of Bucharest, where he held a conference entitled “Tradition, Modernisation, Avant-Garde and Back: the Avatars of Romanian Art Before and After WW1”. Erwin Kessler: “At the 1900 Paris Exhibition, Romania had a schizophrenic presence. On the one hand, it participated with a national pavilion that looked like an oil pipe, like a step into the future. It was industrial Romania. Inside it, however, there were icons, traditional dancers and costumes, and peasant art. And all these in one place. So Romania presented itself as a country which, inside a big industrial cover had a huge traditional body. This schizophrenia was totally backed by reality. Over 75% of the population was living in the rural area. Over 60% of Romania’s output was not industrial but agrarian.”

The young generation of artists was unhappy with the art of that time, so, a year later, on December 3, 1901, some of them formed Tinerimea Artistica, the Artistic Youth. This elitist association was made up of Stefan Luchian, Gheorghe Petrascu and Frederic Storck. Erwin Kessler tells us more about it: “Tinerimea Artistica quickly integrated into the western space, so that the Exhibition of 1904 was the first one to receive a positive review in The Studio, a highly popular art magazine in London, that wrote: ‘Some of the artists whose works have been displayed seem to agree to new theories and artistic formulas.’ This is not much, but at least it’s a pat on the shoulder. In this third exhibition from 1904, the first one set in an international context, Tinerimea Artistica plans for the first time to bring into the Romanian art and exhibitions, a series of artists from the neighbouring countries, mostly from the Balkans.”

By the end of the first decade of the 20th century, Romania was a constant presence in the European cultural landscape. The launch of the futuristic current in literature has an important connection with the Romanian modern poets.

Art historian Erwin Kessler: “In Romania, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the one that launched futurism, was much better known than in other parts of Europe even before February 1909, the moment when he launched the Manifeste de Futurisme, Manifesto of Futurism in the French magazine le Figaro. His work, ever since 1905 – when he started to publish the Poesia magazine in Milan – was a magazine open to Romanian writers from the very beginning. Ovid Densusianu notices the magazine and also Marinetti. In 1906, the year Manifesto of Futurism was published, Alexandru Macedonski was published in Poesia. So Marinetti was known to the Romanian cultural stage.”

The artistic avant-garde emerged, marking the Romanian inter-war period. Insula, the Island magazine, published by Ion Minulescu, was a platform for the Romanian cultural avant-garde: “In the spring of 1912 Ion Minulescu’s magazine, Insula, was launched, a meteoric but essential magazine in which a pro-avant-garde movement is obvious, just as obvious as the disagreement with everything that the system of Romanian modernity meant at that moment.”

In 1924, the Contimporanul movement was founded by Victor Brauner, Marcel Iancu, Milita Petrascu and Mattis Teutsch, that had secured the collaboration of sculptor Constantin Brancusi and of some foreign artists. The first exhibition was held on November 20, 1924 in the hall of the Visual Arts Trade Union, headed by Arthur Verona, Camil Ressu and Ion Theodorescu Sion.

(Translated by Elena Enache)