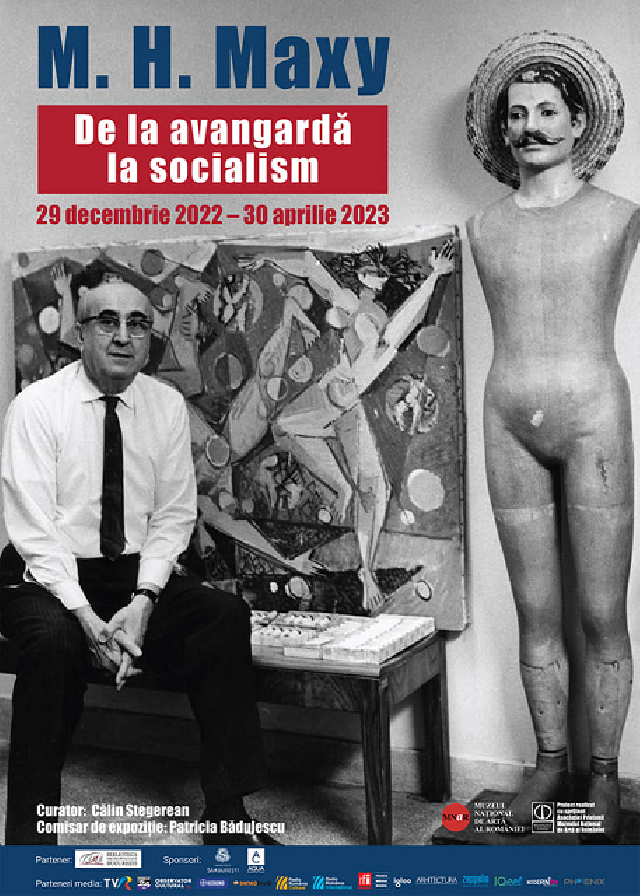

The Max Herman Exhibition : From avant-garde to Socialism

The Romanian Art Museum is hosting, until the

end of April, a new exhibition: M.H. Maxy – From avant-garde to

socialism. Max Hermann Maxy (1895-1971) was a Romanian artist of Jewish

origin, a painter, stage designer, and university professor at the Institute of

Fine Arts. Maxy was one of the most important figures of the avant-garde in

Romania, the founder of the avant-garde magazine Integral, director

of the Romanian Art Museum.

Warning: Trying to access array offset on null in /home/web/rri.ro/public/wp-content/themes/rri/template-parts/content.php on line 53

Warning: Trying to access array offset on null in /home/web/rri.ro/public/wp-content/themes/rri/template-parts/content.php on line 98

Ion Puican,

21.01.2023, 12:09

The Romanian Art Museum is hosting, until the

end of April, a new exhibition: M.H. Maxy – From avant-garde to

socialism. Max Hermann Maxy (1895-1971) was a Romanian artist of Jewish

origin, a painter, stage designer, and university professor at the Institute of

Fine Arts. Maxy was one of the most important figures of the avant-garde in

Romania, the founder of the avant-garde magazine Integral, director

of the Romanian Art Museum.

A complex and powerful personality, but also controversial

and criticized, an artist who created in two distinct times: monarchical

Romania (until 1947) and Romania of the new communist regime (in the second

part of his life). The exhibition presents the artist’s work following the

chronological line of his biography, through paintings, graphics, stage design,

projects, art objects and magazines. We talked bout the exhibition and about

Maxy with the general manager of the Romanian Art Museum, Călin Stegerean, who is also the curator of the exhibition.

He was an exceptional figure of Romanian

art in the 20th century, primarily as a leader, the leader of the avant-garde

movement in the interwar period, the creator of an important avant-garde

magazine, Integral, and of a decorative arts workshop around this

magazine. He was also a very talented stage designer, and worked with various

avant-garde theater troupes. After the establishment of the communist regime,

he held leading positions in the state apparatus, for example, he was president

of the Plastic Fund, and in 1950 he became the director of the first national

art museum of Romania, called the Art Museum of the Romanian People’s

Republic. He supported the avant-garde movement, which he learnt about

primarily in Germany, where he studied and later became one of the organizers

of the great avant-garde art exhibitions in interwar Romania and a contributor

to all the avant-garde magazines of this period, as platforms where the visual

arts met with creation, with philosophy, with everything that meant the renewal

of the artistic language. He was very close to Marcel Iancu. Also, he was very

close to Tristan Tzara, for example, to Ilarie Voronca, Ion Călugăru, with whom

they collaborated on the magazine Integral, actually everything

that was the Romanian avant-garde. Basically, everything was in a very close

connection to everything, because the values and the elites recognized each

other and sought each other’s company. He became a member of the Communist

Party as early as 1942. It was a very troubled period, when the Jewish

population was persecuted, with actions that actually led, or aimed to lead to

the disappearance of the Jewish as an ethnic group. But the vanguard, in

general, brought together people with left-wing convictions. But the transition

to the recipe of socialist realism was done in a somewhat different way than

with other artists. He focused on the underprivileged in Romania. The 30-40s

are proof of this interest in workers, miners, those classes that were not

among the most favored. The exhibition itself, from a conceptual point of view,

takes into account the fact that he was active in two distinct but almost equal

periods: the monarchic period and the communist period, in which he was a

leading figure each time.In the

first part, obviously, he was the promoter of a renewal of the artistic

language that our culture needed, especially since it was also necessary to

connect with the international trends. And, in the second part, he gave signals

related to a certain freedom of creation, a certain freedom of representation,

which somehow brought him back to the elements of expression used in the

interwar period. Of course, without the same scope, without the same breath,

but the fact that these things were possible after a period of ideological

pressure and ideological dogmatism represented a very strong signal for the

guild colleagues.

Călin Stegerean also

told us about Maxy’s activity as head of Romania’s National Art Museum:

Maxy basically set up this museum. You

should know that the best painting repositories are those set up by Maxy in

this museum. He was also the one who, together with other colleagues,

configured the Romanian Art Gallery and the Universal Art Gallery. He also had

the idea of parallel activities, and

this aimed at the general culturalization of the public and the connection of

the arts with life in general.

At the opening

event, the president of the Jewish Communities Federation in Romania, Silviu

Vexler, also told us a few things about Maxy:

Maxy is one of the most complex

figures of Romanian art, but at the same time he is one of the most prominent

Jewish artists in Romania, along with Marcel Iancu, along with Victor Brauner;

thy are, if you like, the most visible symbols and the most easily recognizable

in terms of the presence of Jewish artists in Romania. At the same time, Maxy

is, as an artist, an extremely complex figure, whose creations vary greatly in

the context of the eras in which he worked. It is essential that when his

paintings are viewed, the context in which they were created and in which Maxy

worked is also presented. Even if he is such a prominent figure, at the same

time, unfortunately for the wider society, he is far, far too little known, and

then the fact that such an exhibition takes place at the National Art Museum is

a special chance for those who don’t know much about his work.

Silviu Vexler also told us about Maxy as a regular person, beyond the

avant-guarde artist:

I don’t think one can ignore the person

behind the artist. I think you can get to a point where you understand that

sometimes creation is not related to certain negative aspects of man, but you

can’t completely erase it. If you like, the most famous situation of this

nature is about Wagner. Even today, Wagner is an artist not only extremely

controversial, but, for example, in Israel I think there was only one concert.

At the same time, you can’t help but recognize Wagner’s creation as fundamental

to what opera stands for. However, I do not agree with attempts to erase the

negative aspects of a man’s life just because he was an artist. I believe that

the two aspect are complementary, they must be known in parallel and understood

at their true value. And at the end of the day, it is inevitable that what an

artist thinks will influence their work. That is why I would emphasize that the

added value of this exhibition dedicated to Maxy is that it presents all the

facets of his life. It’s not just a series of paintings on display, which would

have certainly been welcome as such, but the context of the society in which he

created, how his life evolved and transformed, and how they influenced his work

matters enormously. (MI)