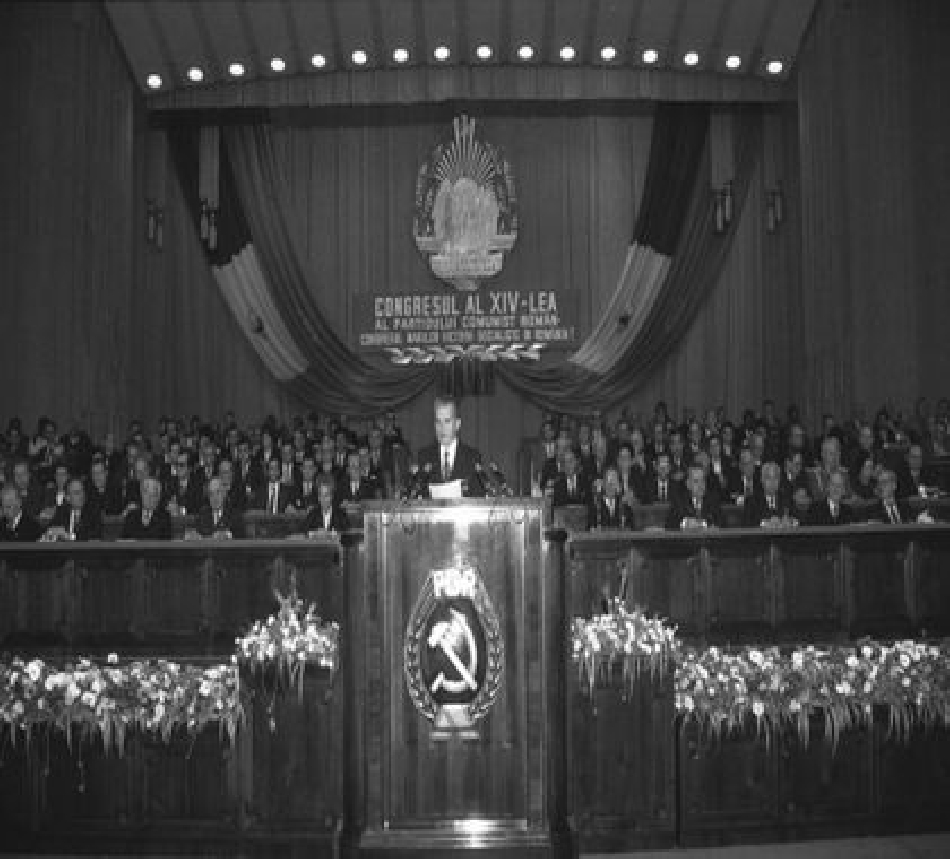

The Romanian Communist Party’s 14th Congress, the last ball

This feature focuses on the Former Romanian Communist Partys 14th Congress.

Steliu Lambru, 04.11.2013, 12:53

The Romanian Communist Party’s Congress of November 20-24th, 1989 was eagerly awaited by Romanians and all those interested in the political future the then leader Nicolae Ceausescu had in store for Romania. Never before had a Congress of the single party been expected with such a considerable amount of interest and fear. Usually, the Party’s Congresses and conferences used to be something ordinary folk would just ignore. People paid heed to such events only because the party and the repressive apparatus forced them to. But that particular congress was one of restlessness, as communist regimes kept crumbling one after the other. As Ceausescu’s regime looked like it would endure forever, Romanians lost all hope for a peaceful change, while the most pessimistic saw no change in store for the country as a whole.

At that time, Romanian society was under the grip of its own frustrations, of the political class’s lack of vision and inability to find a successor for the dictator who had been ruling Romania since 1965.

With the year 1974, the regime’s excessive personalization policy gained its momentum in the 1980s when everything had become unbearable. Against the backdrop of the communist regime’s chronic crisis, an ambition began to burn in Nicolae Ceausescu to see Romania pay its foreign debts. And that lead to harsh austerity measures targeting basic needs such as food and heating.

Engineer Pamfil Iliescu was employed by one of Romania’s largest enterprises at the time called “August 23”. Pamfil Iliescu was also a union leader and all the time he was in contact with people and their needs. Radio Romania’s Centre for Oral History has a recording of Pamfil Iliescu dated 2002.

“In the last five, six or seven years the pointless work we had been doing began to make its presence felt. This became even more obvious in “August 23” plants. As long as there was work, nobody complained. Problems started to surface with the advent of massive investments. In the last years, especially in the last five years, in the mid-1980s, everyone could see that actually everything we placed our investments in was money thrown down the drain. I for one can say that in our department we made investments worth half a billion lei during that period. It was no small amount at the time. Right now it is tantamount to hundreds, if not thousands of billions. And, with no exaggeration, from an investment accounting for more than half a billion we could use nothing!”

The Romanian industry, where a tremendous amount of money had been invested, most of which were loans, was supposed to provide prosperity. On the contrary, it turned out to be a stumbling block for the economy. The cause was the much-too-bureaucratized logic of the communist regime.

“We generally faced many drawbacks, but the biggest one was the lack of money. We had to receive many pieces of equipment or we were given money only to build various pieces of equipment, but that was not enough, because the equipment had to be integrated into a system. And so we received many expensive pieces of hardware that could not be integrated and used, and in the meantime we were required to produce the same amount as before.”

Trade relations with other socialist countries were becoming even more difficult and Romania was running the risk of turning into a closed economic system. Many factories produced more than they exported, therefore the management of many factories was forced to accept products and equipment that had nothing to do with the factory’s specificity. The events of 1989 were also caused by the fact that Nicolae Ceausescu, a rather narrow-minded person, would not give up power at the 14th Congress of the Communist Party. In December 1989 those who took to the streets were the very workers from Romania’s big industrial platforms.

“Roumors had started to go around. It was common knowledge that people said one thing in the meeting hall and something different outside the hall. There was this huge gap between words and actions and people had grown tired of it. They no longer had their weekends free, but what was curios was the fact that they worked more efficiently at the weekend than during the week, because there was no pressure put on them. On Sundays, during breaks, they would even vent their discontent with the system. Without any exaggeration many people expected a change to happen at the 14th Congress and disillusionment was great when they saw that nothing had changed after the Congress. The atmosphere had got very tense and revolt was in the air. I guess many people felt the uprising coming and were not at all surprised when it broke out”.

What followed only one month after the 14th Congress of the Romanian Communist Party was a people’s regaining freedom by paying a blood price. “The last ball in November” is the title of a film by Dan Pita, which shows the final party before the storm, which any authoritarian regime throws before ending up in the trash bin of history.