The Ploiesti Republic

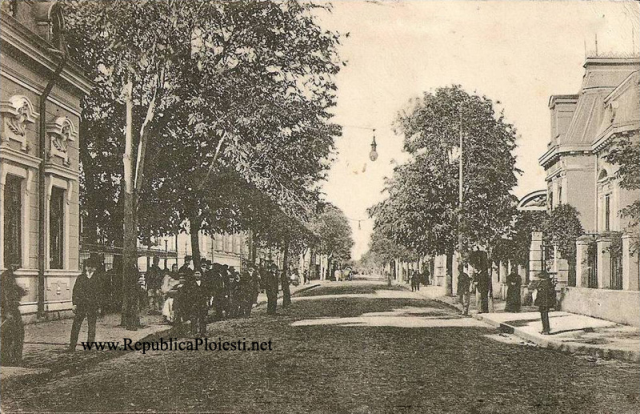

On August 8, 1870, at 4 in the morning, two secret organizations met in Ploiesti to put into play the plan to dethrone Prince Carol of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.

Steliu Lambru, 27.06.2016, 11:49

On August 8, 1870, at 4 in the morning, two secret organizations met in Ploiesti to put into play the plan to dethrone Prince Carol of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, effectively creating a republic. The conspirators planned to take over the local telegraph station in order to rally the army and the population in several large cities. The groups, inspired by the leftist liberals, known as the Reds, were disappointed with Carols rule and the instability within government between 1866, the year he took power, and 1870. One other event that played an important role in this was the French-German war of 1870, which started on July 19, ending in the capitulation of France on May 10, 1871. The war sparked a wave of sympathy for France, resulting in resentment towards Prince Carol, who was German.

The leaders of the conspirators, however, hesitated in implementing their plan, because some of the officers among them had doubts. The rebels in Ploiesti, led by future general Alexandru Candiano-Popescu, carried on with the plan, and took over the telegraph station and the prefects office. Speaking to a few thousand people, Candiano-Popescu declared that Carol was dethroned, and proclaimed himself prefect of Prahova County. After the speech, the mob went to a local military barracks to arm itself. When the unit commander refused to give them weapons, the mob headed to the prison and set everyone free. The action, however, ended shortly after the head of the telegraph office in the town of Predeal cut off the line to Bucharest. That same night, the army rounded up about 400 suspects, including Liberal politicians Ion C. Bratianu, Eugeniu Carada, and Nicolae Golescu. The leader of the rebels was apprehended in the city of Buzau. The so-called Ploiesti Republic ended in little over one day. 41 conspirators were prosecuted, but not convicted.

This short lived but intense episode was satirized by playwright Ion Luca Caragiale in one comedy play and one short story. However, this incident had a special significance in stabilizing Romanian politics.

Silvia Marton a professor with the School of Political Sciences with the University of Bucharest, believes that this rebellion was inevitable, considering the dysfunctions in the Romanian state: “Everything was still possible, everything was open, the protagonists of the rebellion, Carol I, the Conservatives, the moderates, the various liberals, everyone was just starting out, and felt that things were about to be built, there was a volunteer spirit that led to a lot of doubtful things. They wanted to build a parliament and a regime, possibly a republic, but by half measures. At the very least they wanted a regime in which Parliament was supposed to play a very significant role. Carol himself did not yet have a grasp on what was going on. Bratianu was very convinced in what he was doing, and tried to dominate every government he was a part of. The conservatives also wanted to put in a word. In the end, everyone, including the old 1848 revolutionaries, some older, some younger, were very vocal and very convinced in what they were saying.”

We asked Silvia Marton what were the ideas behind the Ploiesti Republic: “We can see this coup, as the prosecution called it, as a reaction against conservatives. Not so much for the republic, but against the conservatives, against the German Carol of Hohenzollern. Two cartoons in The Thorn, a radical liberal publication, a very progressive magazine, are illustrative of the social dimension of this action. This was a social reaction by the proponents of the Ploiesti Republic, who wanted to put an end to special privileges. The noblemen of the old rule were in principle on the side of the conservatives. Lascar Catargiu was a moderate. The old noblemen had preserved their political role, they kept getting reelected, and they were visible on the political scene. There was a strong social and democratic sensibility there. They used the term democratic extensively, in the sense of the end of privileges, of the status of the old noblemen as sole representatives and writers of policy. It was a reaction of the bourgeoisie.”

The Republic of Ploiesti was also a revisiting of the political class’s attitude towards the state, towards reform, towards the figure of the sovereign. Here is Silvia Marton once again:

“Cuza was still alive, though living in exile, and he was elected three times in several districts. He declined, politely, sending letters of refusal; he sent very elegant letters turning down his investiture. However, the liberals, the radicals, the Reds, were Cuzas adversaries. The Reds see Cuza and Carol as being basically the same authoritarian ruler. Carol was an authoritarian, he made decisions without Parliament approval, just like Cuza had refused dialog. The liberals believed that too much power in the hands of the executive was a dangerous trend. They manifested republican tendencies, and wanted the government to answer more to Parliament. Starting in 1870-71, the government started acting with more responsibility, but Carols role was also redefined a few years later, when he made and unmade governments.”

Romanian democracy emerged stronger from the Ploiesti Republic incident; it was the last spasm before the creation of the modern Romanian democratic state. After 1870, especially after the 1878 war of independence from the Ottoman Empire, the country became a kingdom, and gained more stability, with better government.

(Translated by Calin Cotoiu)