The Holocaust in Romania

Romania has its own share of responsibility in perpetrating Holocaust crimes.

Steliu Lambru, 07.10.2013, 13:13

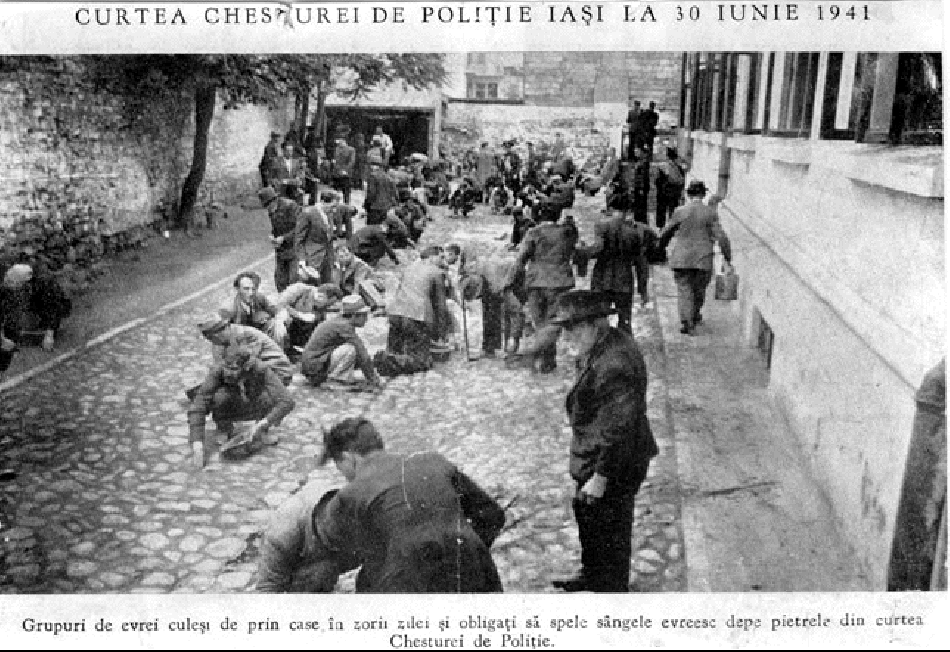

The Holocaust is the utmost expression of hatred that human beings have ever been capable of. From contempt and the racial inferiority rhetoric, the professionals of hatred took the next step, to deportation and methodical mass assassination, which was perpetrated indiscriminately. The victims, for the most part, were Jews and Rroma. Romania has its own share of responsibility in perpetrating such crimes, and took responsibility for that in the 2003 Wiesel Report, where the date was set for the commemoration of the National Holocaust Day on October 9. The Archives of Radio Romania’s Oral History Center have valuable testimonies from people who lived in the inter-war period and during World War 2. In an interview dated 1999, medical doctor Radu Damian recalled a series of anti-Semitic acts at the Medical School in Cluj:

Radu Damian: “As freshmen we had a dissection exam, we studied the muscle and the bone systems. We were supposed to start sectioning, so that we could see the internal organs. And at our dissection table there were also two Jews, Davidson was the name of one of them. One of us asked, “Why, I’ve never seen a single Jew corpse.” And the Jew snapped back, “We never desecrate our people’s corpses!” That was the final straw, something terrible followed. All of a sudden, the room flared up and went berserk, all the bones, all those long femurs from the trays we had there were flung at them. They were cornered, shaking. It took a while before everybody calmed down. “How can you say something like that?! So we’re desecrating our corpses, is that so?!” Then we held a meeting in the courtyard, to decide what we were going to do: whether we should go on strike or take other measures. And finally things calmed down, I just don’t know how, and we all agreed to pay no heed to all that, on condition that they should never speak like that any more.”

Art historian Radu Bogdan joined the communist movement early in his youth. He was not a hardliner, although he had survived a labor camp. In an interview in 1995, Radu Bogdan remembers the camp commander, a true savior, one of those who managed to preserve their dignity in spite of absurd orders.

Radu Bogdan: “True saviors are just like that camp commander of mine, whom I loved and respected a lot, and with whom I stayed on friendly terms. He was an extraordinary man. His name was Petre N. Ionescu, but few people know his name. He was a Councilor at the Bucharest Court of Appeals, and came from a very respected family of magistrates from Iasi. I met him when we reached the Osmancea encampment area, and when we first saw him we didn’t think much of him. His nickname was Mickey Mouse, because he was short, and no one could suspect the tremendous moral resources that man had, his perfect moral integrity. I remember one day when Colonel Corbu came on an unannounced inspection, and found our man with his collar button undone. It was summer, it was hot, and he took us by surprise. He started yelling at him because his collar was undone and was walking about with no tie. But much to our surprise, Ionescu replied, ‘With all due respect, Colonel, Sir, but I’m not going to allow you to speak to me the way you’re speaking right now, let alone raise your voice at me. Please bear in mind that as a civilian I am a high magistrate, a councilor with the Court of Appeals, and I deserve to be treated with respect!’ That man never took bribes. Whenever people needed to find out what had become of the households they had left back home, since they had been forcibly displaced, he allowed them to go and see for themselves, he allowed them to bring gas cylinders back to the camp to be able to cook. Not a hair was touched from those people! There wasn’t a single case of abuse. I admired that man’s courage and moral dignity.”

During those war years, Sonia Palty ended up in a concentration camp and witnessed a heart-rending episode while crossing River Bug. The recording was made in 2001.

Sonia Palty: “One morning, deputy prefect Aristide Padure came to the camp, holding his infamous riding rod, and said: ‘I want all Jews queued up on the Bug River bank! We’ll get you on the other side, to the Germans!’ We all knew that meant death. My father had three arsenic capsules with him, just like the Brauch family did. Mr Brauch gave one of the capsules to my friend Fritz, who was only 20, while I was 15. He told us: ‘Kids, we take the capsules while on the raft. It’s pointless to end up in the Germans’ hands.’ Fritz and I took the arsenic capsules in our palms but we secretly agreed not to swallow them because we wanted to stay alive. So we set down on the bank of River Bug and when we looked up — as most of the time we were looking down — saw some 40 or 50 kilometers away a lot of Gypsies who were drawing their covered carts themselves, as their horses had been taken away. Women with many children got off the carts and the crossing of River Bug began. It was a nightmare. While crossing the river, the Gypsy women on the raft lifted up their children and threw them into the water. Then they jumped in as well. The other Gypsies on the bank started screaming and pulling out their hair at this horrific scene. We had no doubt we would soon be in the same situation.”

The Holocaust was the expression of hatred and obsessions, of general blindness. Its lessons were tough, but the message was clear. Nevertheless, mankind is not yet safe from the temptation of radicalism.