The history of press in Romania. Student press in 1970-1980

A look at student press under the censorship of the communist regime.

Steliu Lambru, 29.09.2014, 12:53

Under direct ideological control, the press in the communist years had a sinuous evolution and coincided with the periods of transformation underwent by the regime itself. In the 1950s and in the first half of the 1960s, the rigidity and dogmatism of the regime forced the press to use a militant, hysterical and aggressive tone. The ideological relaxation in the mid 1960s helped the press change. Although neither the pressure nor the censorship stopped, publications started using a more moderate language and the importance attached to professionalism grew.

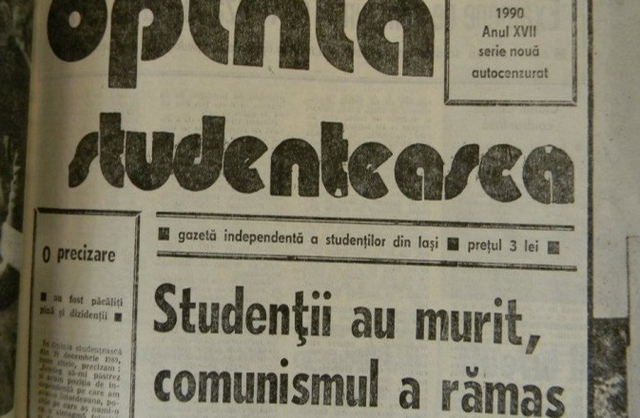

Student press was only an offspring of the central press and emulated its style. The liberalization that occurred in the 1960s targeted student press in particular, with the aim of observing the trends followed by the new generations. New magazines appeared, characterized by a higher level of professionalism as compared to the previous one, such as Echinox in Cluj or Alma Mater and Opinia studenteasca in Iasi. Constantin Dumitru, editor-in-chief of Opinia Studenteasca, which was established in 1974, recalls how the reform of the student press went.

“The early days of student press in Romania go back to the year 1968. It’s no coincidence, it’s a wonderful year that meant a lot to Romania. There had been some pieces of student press before, in 1964, but they were very much in the kolkhoz style, like in the communist billboards. The genuine student press started developing in 1968. To tell you the truth, that happened against an approval given by the Central Committee, and actually from dictator Ceausescu himself, who wanted to see how people would think in a free way. It was an experiment Ceausescu’s personal advisors convinced him to carry out. It was a moment of freedom, of freedom of the press, communist as it was, and I got to know it first-hand. But they could not afford to do that experiment with Scanteia, it would have been nonsensical.”

The new style in communist press also translated into the Press Directorate adopting a more refined way of doing censorship, and journalists had to fight a more subtle battle.

“The Press Directorate was the main censorship body. It was made up of people specializing in deciphering encrypted messages, in seeing what was in between the lines and also to see whether those texts somehow attacked, directly or indirectly, in a subversive way, the political interests of the communist regime. Unfortunately, most of the people working there, with a few exceptions, were just morons who believed the word ‘subversive itself was a threat to communism. I remember how we used to mock and make fun of them when we were students. For instance, we published a poem by Miron Blaga, ‘Day Newborn of My Ancestors’. The comrade from the Directorate did not know what ‘Day Newborn’ in the title meant. It’s simple, I told him, it’s just a pun referring to Danubius and donaris. So, he exclaimed enlightened, this means Danube! And the poem was greenlighted for publication. Whenever we could, we would trick them. And we did that all the time, because they were stupid and uneducated.”

One devious measure taken by the regime was to pass censorship responsibilities to editors in chief. Despite that, however, there were serious irregularities occurring from time to time.

”The Communist Party took a brilliant measure. When I started working as a journalist, at the age of 18, the system of censorship was already in place but I also lived to see it disappear. Why? Because the Communist Party was clever enough to do away with it as it were. So they called us, editors-in-chief and deputies to editors-in-chief and told us: ‘Comrades, starting today there is no more censorship’. We were so happy to hear that! ‘You are going to be the censors’. And our joy faded. Usually, the editor in chief had the final word with respect to approving articles, nobody would dare challenge him. They would become careful only when something special caught their attention, something like the photo of Ceausescu without an eye, or Ceausescu bald. Even so, there were things like that happening. For instance, the president of France came on a visit to Romania at one point. He was very tall, and he was received at the airport by Ceausescu. And the photo depicting this moment was ridiculous. As the French president was way taller then Ceausescu, and Ceausescu was holding his hat in hand, the comrades decided to put a hat on Ceausescu’s head, but they forgot to eliminate the one he was holding in his hand. So this is how he appeared in the Scanteia newspaper, with two hats. A few people were sacked and that was it. Their stupidity made up for the lack of freedom. The intention was not to run a revolution, many times a stupid thing would just come out.”

Today Constantin Dumitru believes that despite the rigors of censorship, journalists were able to work in acceptable conditions. But that only depended on the work ethic of those who assumed their role as journalist with decency.

“We at Opinia Studenteasca did no propaganda at all. I can print those editorials even today, and I’m afraid that they are better written than editorials are today. It also depended on what strategy you adopted. Echinox too had good editorials. To others, an editorial was just a certain façade, behind which they could write what they wanted. Communist editorials would usually pay heed to authorities, it was the kind of publication that worked for the regime. But that did not happen with good student publications. An editorial was something different. We did not do politics. At Opinia studenteasca, the one that I headed between 1974 and 1975, there was no single praising article. Not even one line. So, it was possible.”

The press in the 1970-1980s was representative for the political, economic, social and cultural reality of those years. It went down in history as a chapter in the life of a despicable regime, where society’s expectations were totally different from what the regime provided.