The Asen State

In 1185, the taxpayers of the Byzantine Empire were growing less and less patient, following an increase in taxes ahead of the marriage between Emperor Isaac II Angelos to the daughter of the Hungarian King.

România Internațional, 17.11.2014, 14:07

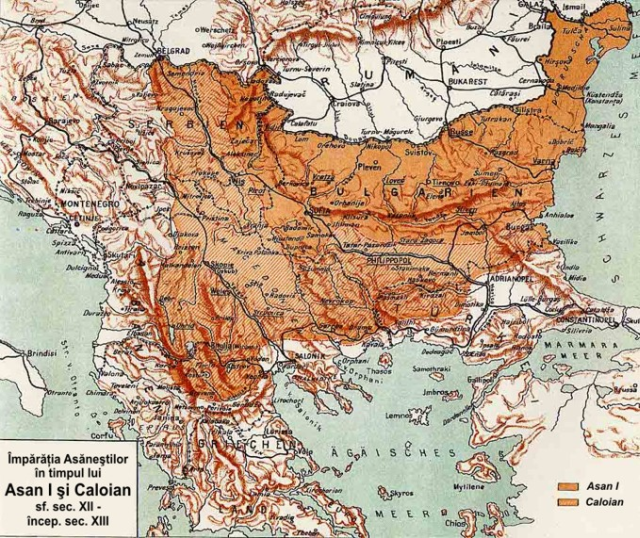

In 1185, the taxpayers of the Byzantine Empire were growing less and less patient, following an increase in taxes ahead of the marriage between Emperor Isaac II Angelos to the daughter of the Hungarian King. Two Romanian brothers, the noblemen Peter and Ivan Asen, the leaders of communities in what is today northern Bulgaria, presented the Imperial Court with a formal protest against the tax increases, a protest which was violently rejected. Having returned to their residence in Veliko Tarnovo, the two brothers started an anti-Byzantine uprising that led to the emergence of the Second Bulgarian Empire, also known as the Romanian-Bulgarian state, and led by the Asenids. This state survived until around 1260, when it fell apart, the successor states being later conquered by the Ottomans in 1396.

A multi-ethnic entity, the Romanian-Bulgarian state comprised at least three different ethnic groups: Romanians, Bulgarians and Cumans. The historian Alexandru Madgearu says it is difficult to create a map of this state based on the available sources:

Alexandru Madgearu: “The Vlachs, the Bulgarians and the Cumans were mentioned together in a number of documents from the time. These sources made a clear distinction on ethnic grounds between those who took part in a military campaign or a siege and the local population. They also distinguished between territories named Bulgaria and Vlachia, so it appears that there was an entity called Vlachia. However, the name Vlach did not refer to the Romanians, because they never referred to themselves as Vlachs. The source in question, namely a papal document, mentions Vlachia as a territory connected to Bulgaria, which means the state was divided into different entities or territories with certain autonomy. All we know with certainty is that the difference between the Vlachs and the Bulgarians is clear in the Byzantine sources, the writings of Nicetas Choniates in particular.”

Although the mediaeval concept of “nation” was different from the modern concept, the Asenids were aware of their own origin. However, ethnic divisions did not prevent the different groups to join forces against the central power. Alexandru Madgearu explains:

Alexandru Madgearu: “Naturally, they were aware of their own ethnic origin, but we have to bear in mind that the idea of ethnic group and nation was different than what we understand by these terms today, starting from the 18th and 19th centuries. At the time, however, we can only talk about membership to a certain group, religion and social category. The only direct source we have, namely the correspondence with the pope, mentions in several places that ‘we are of Romanian blood’. Different ethnic groups participated, for example, in the uprisings. The enemy in these cases were not the Greeks of Greek origin, but the power in Constantinople represented by the tax collectors. All conflicts were generated by fiscal and economic reasons, and it wasn’t the poor who rebelled, but the rich, who were hardest hit by the taxes, and they convinced ordinary people to join their cause.”

Besides its purely economic purpose, the anti-Byzantine uprising also had a mystic dimension that one might be tempted to overlook. Alexandru Madgearu says it was quite common for the Church in the Middle Ages to rally the population for a certain political purpose:

Alexandru Madgearu: “This is how the Asen brothers incited the Romanians and the Bulgarians to start an uprising. They made up this whole story, with Saint Demetrius leaving the Norman-conquered Thessalonica, saying that the Saint abandoned the Greeks due to their sins, and chose to settle in Tarnovo. They built a sort of chapel by the entrance of the citadel and they populated it with lunatics, if I may say so, judging by Nicetas Choniates’ account. It was no laughing matter, given that we’re talking about a millennia-old practice. I have often compared this with the events of 1650 in Moldova, which were quite similar, as described by Marco Bandini. A bunch of people in a state of mystical frenzy started chanting and shouting, “St. Demetrius is with us” and “let’s go to war against the damn Greeks”. Such actions, fuelling a psychological war, were instrumental to unleashing the uprising, since Nicetas Choniates says people were reluctant to go to war”.

Alexandru Madgearu believes the main obstacle to identifying several features of the state created by the Asen brothers was the limited number of historical sources.

Alexandru Madgearu: “There are no sources telling us how many were Bulgarian or Romanian in a city. There aren’t even cemeteries to allow us to make some assumptions. When the leaders were weaker, separatist movements emerge, such as the one of Borila or later the one led by Constantin Asan. It all depended on the tsar’s leniency. If he was lenient, then certain noblemen would proclaim the territories they held to be autonomous, if not even independent”.

The first three rulers, Petru, Ioan Asan and Ionita were of Romanian origin, after which point rulership became increasingly Bulgarian. Even with the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the Asen State remained a distinctive entity in history, which continued to exert power and influence up to its being conquered by crusaders in 1204. The rise of the Ottoman Empire in the early 14th century marked the advent of a new form of state politics.