Romania’s occupation during WW1, in postcards

The amount of literature written about propaganda, war propaganda in particular, is impressive.

Steliu Lambru, 09.11.2020, 14:14

The main role of propaganda is to mobilize citizens during difficult times for a state and its population. The amount of literature written about propaganda, war propaganda in particular, is impressive. Propaganda largely relies on image. Any type of propaganda uses image to glorify its achievements and also to ridicule or diminish the opponents strength. During WW1, propaganda centered on image was used extensively. Romania entered the Great War in August 1916 on the side of the French-English-Russian alliance, following territorial promises after two years of neutrality. But in December 1916, its southern part, or the provinces of Wallachia, Oltenia and Dobruja, as well as the capital Bucharest were occupied by the German, Austrian-Hungarian, Bulgarian and Turkish armies, after four months of terrible fight which claimed the lives of 300,000 Romanian soldiers. Having taken refuge in the east of the country, in Moldova, the Romanian authorities were preparing, with the support of the French military mission and the Russian army, the victorious campaign of 1917 with the battles of Marasti, Marasesti and Oituz.

Occupied in the south, Romania was forced to endure a drastic economic regime of requisitions and restrictions and the propaganda took full advantage of the situation to present the Romanian realities. Behind the realities, however, there was also an everyday life that had resumed under occupation and was caught on camera. Mihail Macri is a postcard collector and expert who has seen thousands of postcards, some of them of Romania during 1916-1918: “Postcards of the occupation armies have appeared. For instance, there was the famous Bulgarian post office in Romania. When the Bulgarians arrived in Bucharest they found some postcards on which they put some stamps of their own. They formed a kind of pseudo-philatelic cards which can now finally be collected, after such a long time. Then, when the German army came, each regiment or battalion had a photographer for its own soldiers, so that they could send letters at home, something which they were allowed to do. The German soldiers did not have any postcards so they would have a photo taken, of themselves together with a peasant woman from Titus for instance. They would send that photo home, if they were not married. If they were married, they would not be photographed in the company of a woman, obviously.”

In 1916, Romania was a country that had come out of the Ottoman sphere of influence for more than a century. During the reign of King Carol I of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, Romania had made notable economic progress such as building a railway network that covered the entire national territory, had a high quality oil industry, had built its capital Bucharest and other important cities such as Iasi, Craiova, Ploiesti, the port cities on the Danube and the port of Constanța on the Black Sea. However, most of the country’s population remained rural, poor and dependent on farming, and the propaganda did not hesitate to capture especially these Romanian realities.

Mihail Macri: “Propaganda postcards were made by the Germans in Romania and they were the ugliest postcards about Romanians that have ever existed. The Germans would not photograph any building in Bucharest, but pick a tavern in Colentina, a district that was not even part of Bucharest at that time, whose damaged roof was supported not by a pillar but by a stick, and had a few tables on the terrace. In the middle of the street, on the way to the tavern, there was a pig in a puddle. The Germans were supposedly showing the state the country was in when they occupied us. There was not one single beautiful and elegant woman in the German photographs and postcards, no national theater or royal palace, nothing. ”

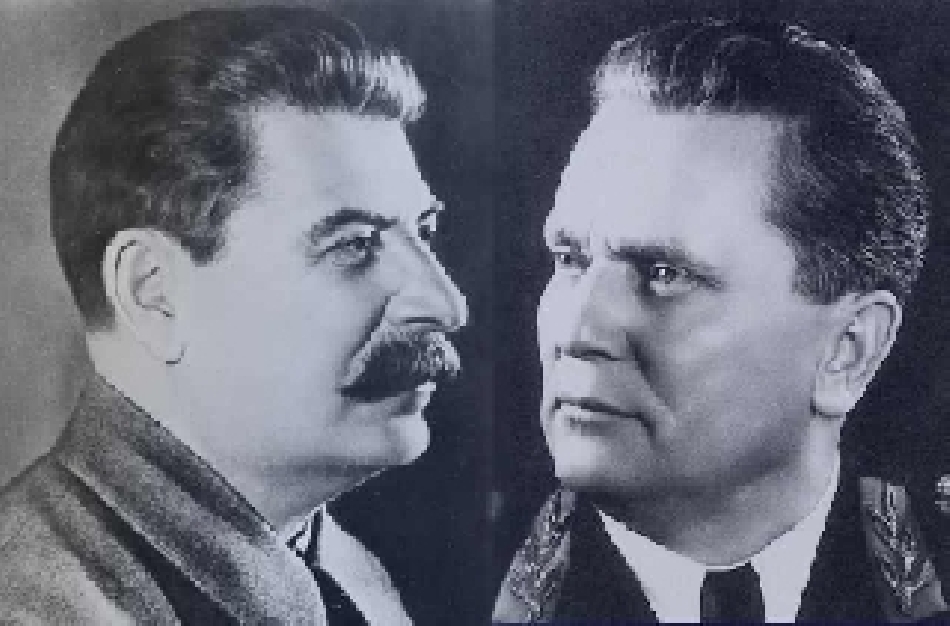

But German propaganda also captured, intentionally or not, parts of the daily life of ordinary Romanians. Mihail Macri: “The only beautiful things they photographed were the fairs, two or three of them being close-ups, which Romania could not do at the time. They were beautiful because they showed all kinds of sellers from that era, including some who were doing their work at home. They had tools in their hands, so as to be recognized by the customers who needed their services. Our postcards were also propaganda, anti-Bulgarian propaganda, and they were the most beautiful such postcards. Paradoxically, the most beautiful Bulgarian books were the anti-Romanian propaganda books. King Carol had the face of a mouse and ears bigger than a mouse, meaning he looked a little like a donkey. Not to mention what the famous Tsar Ferdinand looked like in Romanian postcards, with a huge nose, and usually with a kick in the back. There was no need for text, the message was obvious. The aftermath of the war was also presented in postcards, less in our country than in France, for instance, where many postcards showed what the war meant.”

Seen through the eyes of German propaganda, Romania was, between 1916 and 1918, an underdeveloped territory, a wild land. That was, of course, a gross simplification, an important aspect of propaganda.