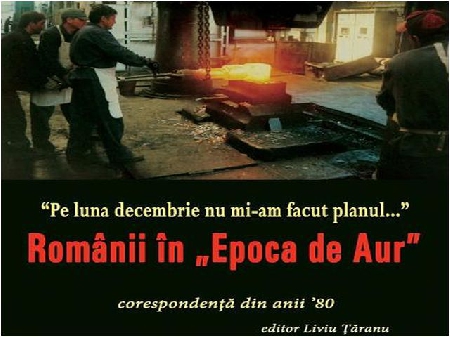

Romanians in Correspondence in the ‘80s

Personal correspondence was one of the preferred sources of information for the Securitate, the political police in communist Romania.

Steliu Lambru, 04.03.2013, 12:26

When searching the archives of an intelligence service, you would expect to find details about state intelligence work, secret operations, details on what goes on behind the scenes in diplomatic work or in politics. Just like many other institutions in communist states, the Romanian Securitate wanted to have full control over society. Personal correspondence was one of the preferred sources of information for the Securitate, using it as part of its culture of repression to determine how to react to certain types of social behavior in one of the darkest periods in Romania’s recent history.

Liviu Taranu, a researcher with the National Council for the Study of Former Securitate Archives published a volume called ‘Romanians in the Golden Era. Correspondence in the ‘80s’. It is a collection of letters sent by Romanians to state institutions in the 1980s. The phrase ‘Golden Era’, a propaganda formula, was part of the language underpinnings of Ceausescu’s cult of personality, and was supposed to show how far Romania had come under his expert leadership. The reality was exactly the opposite. The country was in a deep and widespread material and spiritual crisis, as well as psychological degradation. We asked Liviu Taranu how he would summarize the situation of Romanians in the so-called Golden Era, as reflected in letters:

“Pessimistic, tragic. The most appropriate term is ‘dramatic’. There are letters, documents that bring to the surface Romanian humor, the ability to turn a bad situation into a joke. However, the dominant note is tragic, because people were short on the basic necessities. People, especially with large families, complain of difficulties everywhere, with food, electricity, how expensive living is, as well as job insecurity. You’re probably shocked, but there was a lot of job insecurity in the Golden Era, in the ‘80s. This appears frequently in the letters.”

As historians have documented in their studies, the Securitate was extremely keen on reading people’s correspondence. Letters addressed to institutions were read to the last. Here is Liviu Taranu once again:

“Every letter addressed to newspapers, the party’s Central Committee, any institution whatsoever, generally those in the capital, because we are talking about party and state leadership, were filtered through the Securitate. A lot of them reached their destination, but if their content was too adversarial, they were stopped. We found them in the original in Securitate archives, they never got to their destination. Freedom of expression in writing was curtailed, as shown by these letters. But Romanians did have this recourse, of writing to the upper echelons of party and state, and many of those letters did reach them.”

The dominant sentiment was dissatisfaction with the standard of living. However, there was also a fear of losing one’s job, unimaginable under a regime that claimed to represent the workers, a fear that runs contrary to the cliché that under socialism jobs were secure. Here is Liviu Taranu:

“This fear was quite well founded, because of the general disarray in state enterprises, where changes in the five-year plan were made overnight by state structures which ran the economy, which had a negative impact. There was also the issue of retail, of selling products manufactured in Romania, which didn’t sell. The five-year plan was unrealistic, no one could comply with those demands, especially since manufactures did not have raw materials to execute the plan. People were not getting their salaries on time, the management was trying to cut personnel to reduce expenses and be able to pay the rest of the employees. All this reorganization and endemic macroeconomic problems led to job insecurity and unemployment. Some were just fired and left to their own devices to find a job.”

One of the explanations for the violence that accompanied the overthrow of that regime was the fact that people were gagged brutally. All the communist bloc countries were in crisis, but no other country was so brutal in repressing freedom of expression as Ceausescu’s Romania. We asked Liviu Taranu if he believes there is a link between how brutal the regime was in the ‘80s and the violence in December 1989.

“I have no doubt about that, it happened because tensions had not been released when they should have been. They were festering, and started bursting out in various forms, for instance at the periphery of society. Keeping these tensions under wraps for over a decade, even though things were bad enough even before 1980, resulted in them bursting out violently. Discontent was too great for things to run smoothly, as they did in Czechoslovakia or in other countries in the area.”

Under Ceausescu’s regime, the population had reached towards the end a veritable state of hysteria, which manifested itself in the public space in the 1990s, under the young Romanian democracy of that time.