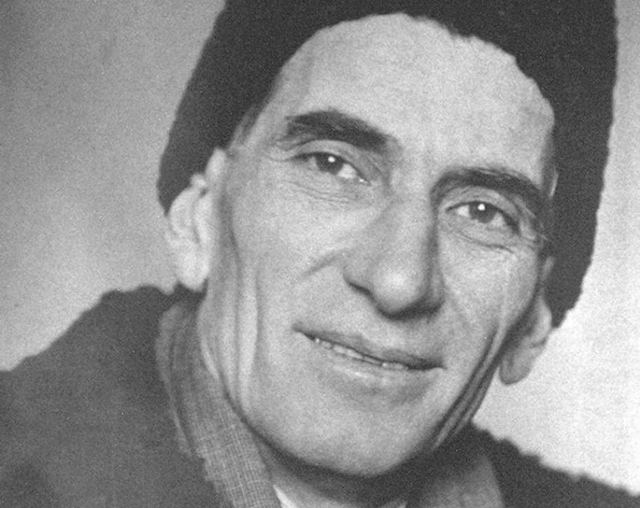

Panait Istrati, the man with no political leanings

The story of one of the most socially engaged writers of the early 20th century in Romania.

Steliu Lambru, 12.10.2015, 13:24

Panait Istrati was one the most complex Romanian writers. Born in the Romanian town of Braila in 1884, he is equally seen as a French writer. His work is influenced by a strong social message, laying a significant emphasis on the world of the proletariat and the disenfranchised. Istrati adhered to communism from the early days of his youth. However, he was one of the first to have broken away with its ideology after his visits to the Soviet Union. Professor Ioan Stanomir will now be explaining Panait Istratis political and intellectual affiliation.

Panait Istrati veered towards communism having adopted a stance which was very familiar to a great many European intellectuals: the stance of dissatisfaction and social revolt. We should not forget that Panait Istrati was, over and above anything else, a socialist, he was very close to Cristian Rakovski, he bore witness to Romanias strikes in their early form at the turn of the 20th century, and that his family background was marked by hardship and marred by a dire social condition. All that had built into Panait Istratis intellectual character. And theres also something else we must take into account: he was very familiar with the French intellectual milieus, where he was viewed and rated as a voice for the downtrodden and the underprivileged. In that respect, Istrati and Gorki have diverging and similar destinies. Istrati was a communist, then broke with its ideology and turned lucid. Gorki befriended the Bolsheviks, supported them, he was a friend of Lenin, set off in exile in the early stages of the Bolshevik power, he returned and would be signed up by Stalin. Istrati and Gorki have something in common: European fame and an ideological commitment, the idea of a writer assigned to fulfil his mission by the social class he comes from.“

In 1927, Istrati visited Moscow and Kiev. In 1929, he would travel to Soviet Russia again and it was then that the veil was lifted form his eyes, which basically meant the communist regime was far from what it advocated in theory. He wrote ‘Vers l’autre flamme. Confession pour vaincus, ‘To the Other Flame. Confession for the Defeated where he highlighted the communist regimes abusive actions and which came out as something utterly shocking. When the book was brought out, Istrati would be isolated and accused of fascism. Ioan Stanomir again.

A trip to the Soviet Union is not necessarily a reason for an awakening, it could be an even greater opportunity to go blind once again. The exception confirms the rule, since there are very few travellers who, once they got to the Soviet Union, lacked the strength to go beyond the veil they themselves had put before their own eyes. Let us not forget Beatrice and Sidney Webb who visited the Soviet Union and returned with eulogizing and delirious texts about the Soviet Union. Let us not forget Herbert George Wells visited the Soviet Union and it looks like the visit had no impact whatsoever on his literary outlook. There are two names we need to mention as regards this so-called awakening. They are Panait Istrati and Andre Gide. Both reached the Soviet Union and both wrote books that placed them in a very delicate situation. Let us not forget the fact Istrati was mainly accused of betraying the cause of anti-fascism and the cause of democracy by bespattering the Soviet Union. The USSR was the main bulwark for the anti-fascist and democratic fight at that time, from the viewpoint of the communist imaginary.

But it was against the Stalinist crimes and not the communist ideology Panait Istrati rose. An admirer of Trotski, he would write he no longer adhered to the revolution until that was made “with a pure, with a childs soul. Ioan Stanomir believes Istrati actually broke way with Leninism.

Trotski was an armed prophet, he was armed against his own people. The Red Army, which Trotski created, was an oppressive tool used above all against the Russian people. It was the Red Army that destroyed the peasants class in the civil war. Trotski stood out as the anti-bureaucratic and anti-totalitarian alternative from the perspective of the radical left. Istrati broke with Leninism, better said, he noticed a huge rift existed between what leftists in general perceived as being Leninism and what the anti-Stalinist leftists perceived as being Stalinism. Istrati never denied his far-left convictions, its just that he took a step back, noticing that in Stalins Russia Leninist principles were disregarded. Panait Istrati, just like his peers, fell prey to a terrible illusion: the one stating that Leninism was different from Stalinism and that Leninism was not a form of totalitarianism.

How did the communist regime in Romania use Panait Istrati? Ioan Stranomir.

“Panait Istrati became an asset for the communist regime in Romania, mainly after the 1960s. It was not without good cause that such a thing occurred at a time when the French-Romanian cooperation was being strengthened. Its quite certain that Istrati was something the communist regime took advantage of, when the relationship with France was re-launched. Panait Istrati was a child of France, a Gorki of the Balkans promoted by the French, by the far-left literary circles, and French communists would come to Romania to shoot their productions and to engender a democratic-popular Romanian filmmaking industry. A wave of translations would follow, since part of Istratis texts were in French. If we take a look at the ‘Everymans Library collection which includes outlines of his life and work, we can notice the care with which the episode of Istratis apostasy is placed in a context, described as a transient spell, one which had been however balanced out by Panait Istratis substantial contribution to the workers movement.

Just as history has shown, Panait Istrati was one of the defeated. A defeated man who, like many before him, pursued happiness for the oppressed but who only succeeded in sinking society into deeper misery.