Freethought and anticlericalism in Romania

Throughout history, challenging the authority of the clergy was often accompanied by movements that sought to reform religion.

Steliu Lambru, 10.04.2017, 13:26

By no means synonymous and never fully convergent, freethought and anticlericalism more often than not found common grounds in terms of ideology. Throughout history, challenging the authority of the clergy was often accompanied by movements that sought to reform religion and even called into question the very existence of God and spirituality itself. The radical strands of freethought and anticlericalism often had an important militant component, aimed at changing the world and instating happiness and equality for all. Modern versions of freethought and anti-clericalism are rooted in the 18th century thought, when Enlightenment philosophers placed reason at the center of man’s life, trying to free his mind from irrational religious dogmas. Thus, curbing the power and influence of the Church both within the state and at society level was cornerstone of the rationalism as an epistemological approach.

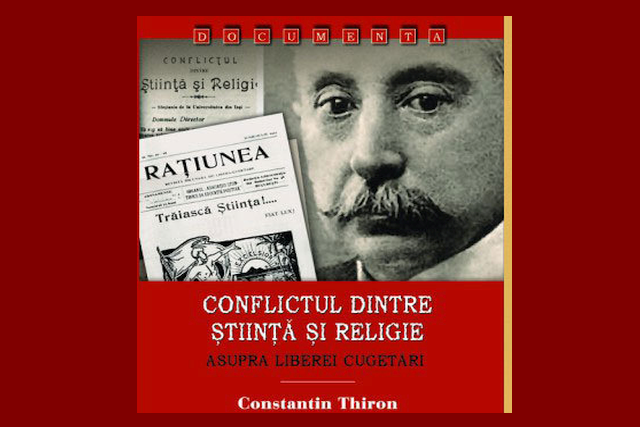

In Romania, modern freethought and anticlericalism emerged in the second half of the 19th century, spreading to the radical liberal and socialist groups. Darwinism and materialism underlay the struggle to reform society of such people as medical practitioners Constantin Thiron and Victor Babes and philosopher Vasile Conta.

Marius Rotar, a researcher with the December 1, 1918 University in Alba Iulia, says freethinkers made up the hard core of anticlericalism and secularism in Romania: “The most important advocates of anticlericalism in our country, but also in Europe and the United States, were freethinkers, representing a cultural, political movement of atheist convictions that were trying to free individuals of prejudice and religious and scientific fallacies. Their main purpose was the separation of Church and state, which happened in France in 1905 and in Portugal in 1911. There are a few important champions of freethought, such as Robert G. Ingersoll in the United States and Charles Bradlaugh in Great Britain. The International Federation of Freethought was founded in 1880. How does anticlericalism manifest itself? At individual level it translates into adopting a deeply anti-religious mindset. In the case of freethinkers, socialists, radical liberals and freemasons you can notice three distinct canons: the secular oath, which was settled in Romania only in 1936, civil marriage and third and most importantly, secular funeral ceremonies, where interment is performed without the service of a priest”.

Freethought and anticlericalism appeared in Romania much later as compared to the West. Marius Rotar explains: “There are a few exponents of anticlericalism in Romania, the most important of whom is Gheorghe Panu, in late 19th century. Panu harshly criticized the Romanian Orthodox Church in his paper, ‘Lupta’ — ‘The Fight’. The famous Anthology of Atheism in Romania picks him as the one of the vocal promoters of Romanian atheism. Despite this fact, in 1910 he is buried with a priest celebrating the funeral service. Nicolae Leon too was buried in the presence of a priest. From this point of view, Thiron went all the way, in the sense that in 1905 he expressed his will to have a secular funeral service, which happened later in 1924”.

Romanian freethinkers expressed their views in the press, often using strong language, bordering insult, and were forced to defend their opinions that were at odds with those of the powerful majority. Separating citizens from religion and keeping morality and religion distinct were fundamental points on their agenda. The actions of socialists Stefan Gheorghiu, I.C. Frimu, Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea, Panait Istrati, who all demanded a secular interment, were deemed as exemplary for the others.

Marius Rotar again at the microphone: “In 1913, Thiron published the following letter in ‘The Morning Paper’: “Congratulations to the young couple who preferred to unite only in civil matrimony. My sincere congratulations to you for your courage to steer clear of the nonsense and manipulations preached by the Judeo-Christian religion, by bibles and Gospels, by books of prayers and the Talmud’. The reaction of the Romanian Orthodox Church read in no uncertain terms: ‘is there no one who can apprehend and shake up this man who makes bold at insulting the greatest part of the Romanian nation, who doesn’t share in his beliefs?”

Perhaps the most radical of Romanian freethinkers and anti-clericals was medical practitioner Constantin Thiron (1853-1924), who taught at the University of Iasi. A field medic in the Balkan War of 1913 and in the Great War, Thiron was the champion of Romanian freethought. Marius Rotar explains: “Thiron’s watch was engraved with the following: ‘death to all gods and hail freethought!’ Thiron stood by his dictum until his last breath. In 1913 Thiron set up his secular tomb in Iasi. It is the first secular tomb in Romania, and it’s steeped in symbolism. The same year, at the Eternity Cemetery, an agnostic monument was raised in the memory of Vasile Conta. Thiron made his will three times, in 1905, 1913 and 1921. When you’re young, you tend to be more rebellious. Thiron draws up his first will at 52 years of age, in the post-Prometheus phase. It contains some of the ideas he advocates, as well as a quote from an article he published in ‘The Opinion’ paper: ‘only Judeo-Christian fools fear death’, Thiron writes, ‘due to the gibberish and ineptitudes of the bible and the Gospels, imposed by the clergy in order to crush their dignity and courage and make them humble and indebted slaves to the clergy of various religions”.

Freethought and anticlericalism had a limited social scope in Romania, striving to introduce the Romanian public to various contemporary schools of thought.