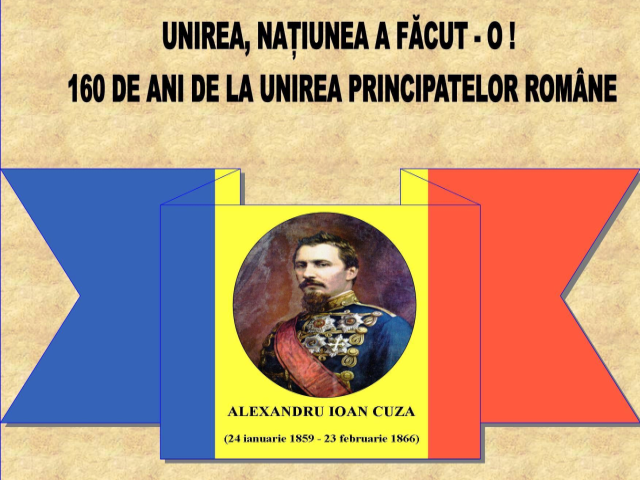

160 Years Since the Union of the Romanian Principalities

The Union of the Romanian Principalities, Moldavia and Wallachia, on January 24, 1859, was made by domestic pressure, but also under propitious international circumstances

Steliu Lambru, 04.02.2019, 15:20

The Romanian national project could not have existed without a rearrangement of Europe to begin with. One of these circumstances was the fact that the Danube, one of the most important European waterways, came to the attention of major powers, like France and Germany. This major west to east throughway was reevaluated at the time as a conduit of civilization and democracy, freedom and emancipation of nations on the Old Continent from under Oriental despotism. The assault of Western powers to liberate the Danube had as one of its effects the union of the Romanian Principalities in 1859.

However, this union, especially if we keep in mind its eventual result of forming the Romanian state, did not lack controversy. Historians acknowledge the difficulty of the union of January 24, 1859, with identity conflicts that lasted until the interwar period.

Historian Adrian Cioflanca said that the late 1850s was a time when two major social ideas clashed: “Around 1859, two major ideas clashed: modernization and union, which had been floating around independent of each other until the 1848 revolution. Up until 1859, union did not automatically imply modernisation. After the failure of the 1848 moment, revolutionary energies were re-invested in a political project such as the union, suborning to it modernization. This national project demanded political and national unity as congruent aims. The union was seen as a panacea for all the issues in Romanian society. This desperate and oversized investment explains the widespread support that this project had during the time, and the disappointment that followed. The union did not necessarily bring about an improvement in the domestic situation.

Some historians believe that the Czarist expansion to South Eastern Europe, along with the annexation of the portion of Moldavia from between the Prut and the Dniester by Russia in 1812, compelled Moldavian elites to consider more and more seriously the union with Wallachia.

Historian Andrei Cusco from the State University in Chisinau is not ruling out that possibility: “There were multiple versions of events, and what happened was just one of them. We can speculate regarding the alternatives, such as what would have happened if the Russians had taken over the entirety of Moldavia. We cannot rule out the fact that the entire Romanian national project wouldn’t have happened at all. It is unlikely for the Russians to have stopped at the Dniestr, this was the boundary they had reached as early as 1792. This version of events created a dilemma for the elites, but less so for the population. Starting in 1812, the rest of Moldavia went along with the idea of uniting with Wallachia as a counterweight against Russia. In a way, the 1812 annexation prodded along the process of Moldavia and Wallachia uniting, and this was a positive outcome. But from the point of view of the Bessarabians, this version of events created new and more difficult issues.

There was the issue of the organization of the new state at that point. Would it be a French model centralized state, or a federal or confederate model, like the German state? These were the questions that the unionists had to grapple with, on both sides. In the end, centralism prevailed.

Andrei Cioflanca: “After 1859, in setting up the newly formed state, the choice for the political and administrative arrangement was a centralist one. Culturally, the choice was identity uniformity. However, centralism was not the only option for organization in the early 19th Century. Separatists favored confederation, a state model that respected regional identity and interests. It is interesting that confederate projects were pushed in the initial stage in revolutionary milieus, which later on opted for unionism. Federalism was an attempt to remove East European national identities from the control of empires, and organize them into new political forms. Before 1859, there were a few important creators of so-called ‘politograms’, most of them unionists, who pushed for administrative decentralization. Among them were Mihail Kogalniceanu, Nicolae Sutu, Ion Heliade Radulescu, Constantin Heraclide, and first and foremost Vasile Boerescu.

The two sides, the unionists and federalists, the latter referred to as ‘separatists’, threw their respective hats in the ring with specific arguments. While the unionists believed that centralization would lend strength and coherence to the future state, the federalists believed that strength lies in decentralization, with equality between the two entities, Wallachia and Moldavia, which had formed the state in the first place.

Adrian Cioflanca: “The two principalities had undergone separately a process of centralization, which culminated in the Organic Regulations of 1831-1832. At the time of the union, with the available political and administrative experience, the only practice that could claim some tradition was the centralist one. Modernization as a theme resulted in the newly formed community being conceived against the background of a lack of profound political debate regarding the internal organization of the state. There was also the issue of foreign pressures and threats. The most important centralizing action during Alexandru Ioan Cuza’s rule comes in completion to the international recognition of the union.

On January 5 and 24 1859, in Iasi and in Bucharest, Alexandru Ioan Cuza was elected ruler of both Moldavia and Wallachia, which was just the beginning for the country that we see now.