Teaching the history of communism

Romania teenagers can learn more about their countrys recent past in an optional course about the history of communism.

Christine Leșcu, 05.03.2014, 13:19

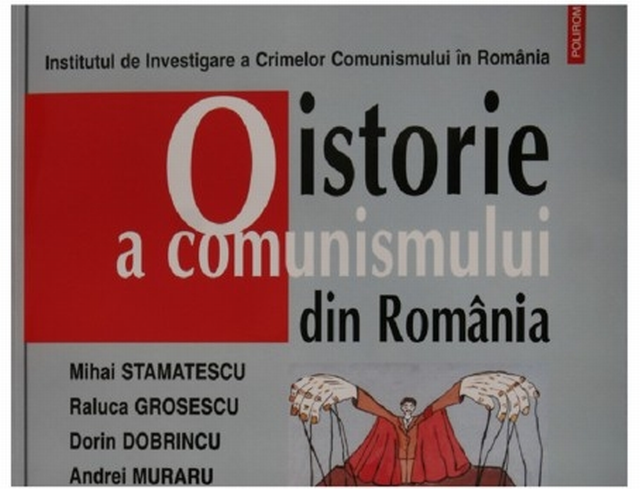

The history of communism was introduced as an optional course in the high school curriculum in 2008. The decision came as a result of a recommendation made in the final report of the Presidential Commission for the Analysis of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania. The first textbooks dealing with the history of communism targeted 11th and 12th grade students and were drafted together with the Institute for the Investigation of the Crimes of Communism in Romania and the Memory of Romanian Exile. The former executive president of this institute and a co-author of the textbooks, Adrian Muraru, told us more about their content:

“The textbooks cover the period between 1947 and 1989 and look at issues such as daily life during communism, the economy, cultural life, minorities, the political regime, repression, etc. It wasn’t easy, of course, to deal with such a variety of topics, but we focused on short texts and a lot of historical sources, from archive documents to oral history materials. Textbooks come with a DVD containing footage from the Romanian Television archive dating back to 1988. In our opinion, these textbooks are very well designed in that they also allow students to do their own research. We did not want to do propaganda or impose a single view on the history of communism in Romania. This is why the name of the textbook is ‘A History of Communism’, because we can have several histories of communism depending on who conducts the research.”

146 schools across the country are teaching this optional course today. Since its inception, it is estimated that 3,000 students have taken this course every year. The Institute for the Study of the Crimes of Communism also holds training courses with history teachers, because teaching this course implies different methods and information than a normal history course. The need for information is great, as indicated by different surveys.

One such study run by the institute in 2010 concluded that Romanians are ambivalent about the communist period. 47% of respondents viewed communism as a good idea, but badly put into practice, while almost 30% believed it was a bad idea altogether. Three years later, in a poll run in December 2013, 47.5% of Romanians believed that Nicolae Ceausescu was a politician with a positive role in Romania’s history, while 46.9% believed he was a bad person. Similar percentages apply to his predecessor as head of the Romanian Communist Party, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, who was viewed positively by 42.3% of respondents and negatively by 39.1%. This explains some of the opinions held by students before starting the course. Mihai Stamatescu, a history teacher and co-author of the textbook, told us more about this:

“Generally, children get their information from their families, neighbours, the community at large and, to a lesser extent, also from the media. The information they have is generally what they get from the public space, such as ‘Communism was good because we all had a job and a place to live’. Children come to school with this information, and suddenly find out that what they know doesn’t fit. The explanations offered by the course and the recent history studied in school shine a different light on reality. Children suddenly realise that their parents’ nostalgia does not necessarily refer to the communist regime, but simply to their youth. If you have arguments and provide proof, if you challenge them to read historical sources, if you explain to them what manipulation and propaganda are, children will understand what happened to their parents. They are willing to think logically and critically about all the things that happened.”

When students start to understand the realities of everyday life under communism, they become more and more interested in the course. Plans are under way to teach this course to younger children as well. Here is Mihai Stamatescu once again:

“We put together a material called ‘Human Rights in Recent Romanian History’ which targets children up to the 8th grade and can also be used by younger children. We thought the best way to provide children with information about the communist regime is from a human rights’ perspective.”

Of course, a single optional course cannot change the perception of an entire society. School activities should be accompanied by various other initiatives to inform the public about communism. Andrei Muraru explains:

“It also depends on what we do as a society in general. Our counterpart in Poland, the Institute of National Memory, has over 2,000 employees, while we have only 36. They have a budget of over 60 million euros, while we have only one million. They started doing what we do today as early as 1999, and the results have started showing after 10 or 15 years of massive investment in education. The investments were not made only in terms of courses, but also in terms of games for children and teenagers, school curricula, film screenings, conferences and books. Everything depends on the resources society is willing to invest in this area.”