Urmuz’s absurd work

Romanian inter-war writers, revisited

Christine Leșcu, 09.04.2023, 14:00

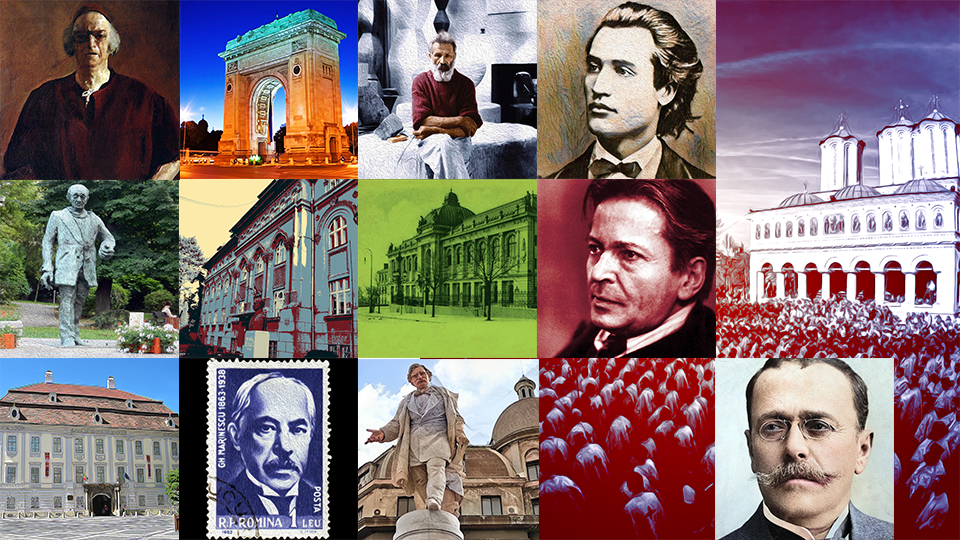

The year 2023 marks a twofold celebration of one of the most uncanny and influential Romanian writers, Urmuz. Actually, we commemorate 140 years since his birth and 100 years since his death.

Urmuz was born in 1883. His non-conformist pieces of writing acted as precursors of Dadaism, but also of surrealism and the theater of the absurd. Furthemore, Urmuz’s writing extended it influence to contemporary post-modernism. Notwithstanding, and despite his posthumous fame, Urmuz lead a basically unassuming life with tragical end: Urmuz committed suicide.

Gheorghe Păun is a mathematician. Equally passionate about literature and Urmuz’s writing, he will now be providing an outline of a writer whose real name was Demetru Dem. Demetrescu-Buzău. Urmuz was his pen-name.

He was born 140 years ago in Curtea de Arges. His date of birth was March 17, according to the Julian calendar. So on March 30 we commemorate him for a second time around. He came into this world in the family of physician Dimitrie Ionescu-Buzău. He was a medical doctor with the city hospital, he also taught at the Theological Seminary. The physician had settled in Curtea de Arges earlier, yet in 1888 the family relocated to Bucharest. Urmuz was in Curtea de Argeș for a mere five years or thereabouts. In Bucharest, he completed his high-school studies with the Gheorghe Lazar high-school. And it’s interesting to note that there, among some of his colleagues were future writers Vasile Voiculescu and George Ciprian, both of them were born in Buzau or close by, just as Urmuz ‘s father was also born there, apparently. In their memoirs, Voiculescu and Ciprian tell the tale of the practical jokes they did together, in the days of their youth.

A restless character, the future writer had been going through several educational experiences; he found it really hard to have a place in the society, but also in the culture of his time.

Here is Gheorghe Paun once again.

He pursued a Medical Faculty programme for one year, strongly urged by his father. Yet he couldn’t cope. Then he pursued a Law study programme. He was a judge in several communes in Arges, Dâmbovița, Dobrogea. In the long run, he came to Bucharest, being appointed a court clerk with the High Court of Cassation. He was dead set on coming to Bucharest. He was in love with music. He could play the piano from a very early age. His mother played the piano as well. And he arrived in Bucharest. He began to write in 1907, 1908, something like that, his sister told us. He sent his texts to Ciprian, who used to read them in the cafés across Bucharest. The Romania avant-garde had already been born, but also the European one. And he definitely kept himself abreast of a lot of things. Too bad he died an untimely death. He committed suicide in 1923, for unknown reasons. Yet some explanations for his gesture still hold water. From what I’ve read, he was ill, or so it seems. Ciprian also said he was on the verge of paralyzing. But then again, in another move, it was kind of trendy among the avant-garde writers of his time to take their own life. Quite a few of them did that, or they tried, at least. He may have been slightly depressive as well. He had been a little bit fearsome from childhood because of his father’s authority. But I don’t think that was crucial, it was the illness everybody talked about.

The only man of letters who recognized his value as a living writer was the poet Tudor Arghezi, who also published Urmuz, in 1922, in the magazine he ran at that time, Cuget Romanesc/Romanian Thought. The two texts by Urmuz published there were Algazy & Grummer and Ismaïl and Turnavitu, texts the author refined till the last moment, just as Gheorghe Paun was keen on telling us.

He somehow complained about the boring life of a court clerk. He was dead set of making music. He also pursed a study program at the Conservatory for one year. His musical scores were lost, unfortunately. He wrote the way he wrote with a total respect for the text. He used to produce a couple of dozens of versions for a text, according to another avant-garde writer, Sașa Pană. His personality is hard to outline. He knew loads of things and, then again, he was aware of his value. He had a total respect for the text, to the comma. Arghezi, who published him, tells us how he turned up at night asking if the commas were in the right place or not. What he did was different from Tristan Tzara’s dada bits, who took the words out of the hat, putting them on the page.

After his death, Urmuz was discovered by the inter-war avant-garde writers; his mini-work was partially published in the 1920s, in the Contimporanul magazine, edited by Ion Vinea and Marcel Iancu. Then in the 1930s, writers Sașa Pană and Geo Bogza, in the UNU/One magazine published most of his texts they obtained from Urmuz’s sister. A great many of his writings were lost, however, but what has been preserved is more than enough to ensure Urmuz a status he would have never imagined for himself, a status that was reconfirmed mainly after the 1989 Revolution. However, during communism, Urmuz’s biographical traces of his native town were annihilated, such as the family house.

Mathematician Gheorghe Paun once again.

It only exists in an image that was retrieved from partial photographs and reconstructed on the computer. It was demolished in 1984 when a little block of flats was built there. Of course, nobody made much about Urmuz in the time before the revolution. Very few people in Curtea de Arges knew about Urmuz until two or three years ago. Yet now many people know about him, as four years ago we had a beautiful cast bronze plaque installed on the wall of the block of flats that was built where he was born. Now a bistro cropped up in Curtea de Agres, known as At Urmuz’s, with pictures of Urmuz on the inside and on the tables, with a brochure of Urmuz’s complete works. If someone wants to read, if they want to take it home with them, they can take it.

Among Urmuz’s posthumously published texts, prose and verse, there are Chroniclers, The Funnel and Stamate, the Fuchsiad and Leaving Abroad. Of them, The Funnel and Stamate was also successful abroad, being translated into 23 languages a long time ago. (EN)