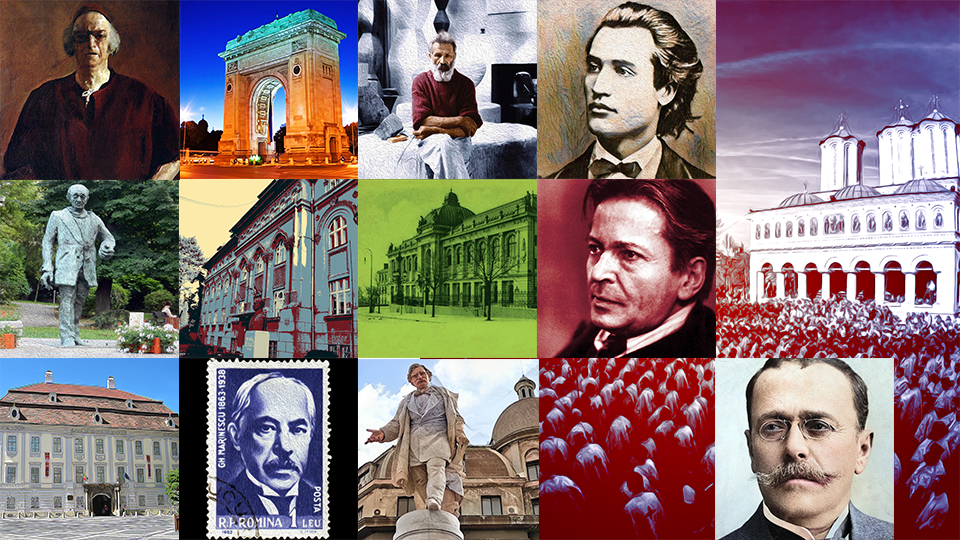

The Lost Synagogues of Bucharest

Romania's capital used to have a Jewish neighborhood which has undergone massive changes in time

Steliu Lambru, 04.01.2020, 15:19

Romania’s capital used to have a Jewish neighborhood which has undergone massive changes in time. Some of the affected buildings were also the synagogues that were demolished, which is significant given their importance as centers of community life.

Jews started being documented as living in Bucharest around the middle of the 16th century, during the reign of Prince Mircea Ciobanul. They were the descendants of Jews exiled from Spain in 1492. Sephardic Jews had taken refuge in the Ottoman Empire after the exile, and founded the Jewish community of the present capital of Romania, with its own culture and civilization. The Sephardic community centered around the Popescului neighborhood, an area that starts behind Union Square, in the very center of Bucharest, spreading east. Naturally, a well-knit community has its places of worship, and synagogues have been at the very heart of Jewish life in Bucharest. Unfortunately, one of the first documented events in the life of this community was a tragic one. On 13 November, 1593, the then prince of Wallachia, Michael the Brave, started his anti-Ottoman campaign by killing everyone he was owing money to, among them Turkish and Jewish creditors.

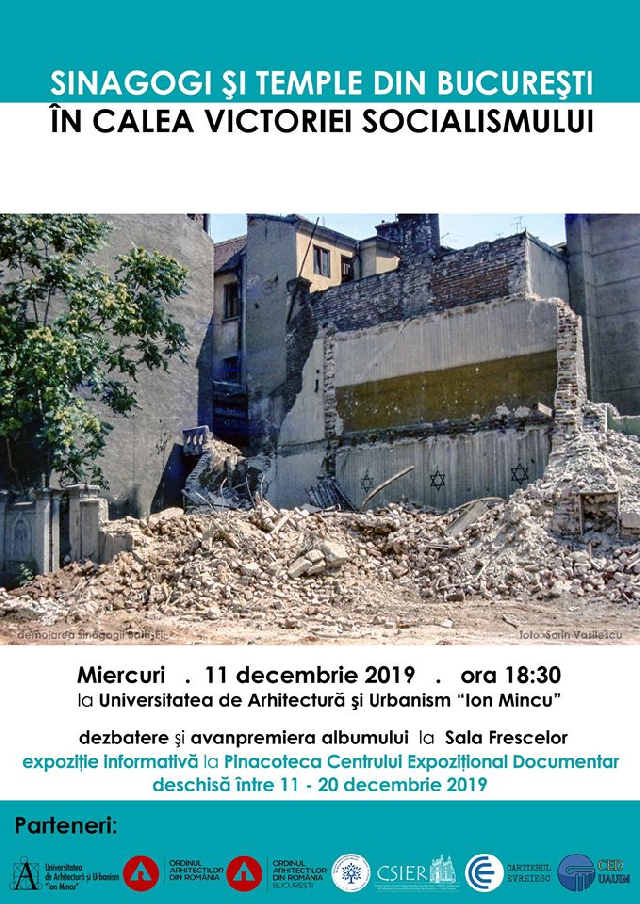

The policy of reconstruction and urban planning of Bucharest carried out by the Ceausescu regime after the devastating earthquake of 1977 went way beyond the need to reconstruct the part of the city that had been leveled. The worst affected by the reconstruction were the neighborhood called Uranus and the Jewish quarters. They were two of the oldest neighborhoods in the capital, and lost priceless religious buildings and homes. Cezar Petre Buiumaci is a historian with the Museum of the Municipality of Bucharest, and he told us that the moment of greatest transformation in the 20th century history of the capital was March 4, 1977:

“The beginning of the tragedy for these neighborhoods, the earthquake of March 4, 1977, provided Ceausescu with an opportunity to radically change the face of Bucharest. In the process of reconstructing the city, Ceausescu tested the population’s reaction by demolishing the Church of Ienei. This was done very quickly, in spite of the weak protests on the part of a few notable people.

Recovering the memory of these buildings and historical and urban research of lost neighborhoods can only be done by photographic archival material. The inhabitants of the condemned buildings have left behind pictures of their homes, which were soon to fall prey to bulldozers and wrecking balls, as well as pictures of their streets and their neighbors’ homes. Among the victims of systematization were synagogues. The few remaining ones have been obscured behind giant concreted blocks of flats typical of Communist regimes, such as the Grand Synagogue. Anca Tudorancea with the Wilhelm Filderman Center for the Study of Jewish History in Romania coordinates the project to study the temples that were razed to the ground:

“Two synagogues were spared, and are now museums for the community. This is a story worth telling, the way they were saved, since reconstruction plans had them condemned. Fortunately, the Holy Union temple, which is now the Nicolae Cajal Jewish History and Culture Museum, is one of the happy stories, because it was not only spared, but thanks to it, an entire half of a street was saved. This is Mamulari Street, a religious street, a street that used to be mostly tailor shops. It is a street with modernist houses, where historians can also find commemorative plaques related to other Romanian personalities, such as Corneliu Coposu, who used to live there.

The list of lost temples is overwhelming. The Fraterna temple, on Mamulari Street, built in 1863, place of worship for the guild of tailors, was affected by the great earthquake, and was taken down in 1986. The Cahal Grande temple on Negru Voda Street, built in 1819, was reconstructed in 1890, was devastated by Legionnaires in 1941, and was demolished in 1987. The Carpenters’ Temple, built in 1842 and reconstructed in 1895, also devastated by the Iron Guard, was demolished in 1984. The Adath Ieshurim Synagogue, close to the Carpenters’ Temple, an Orthodox temple built in 1915, was also demolished in 1984. The Gaster Temple, on Sticlari Street, was one of the most modern buildings of its time, a place of worship for the Jewish elite of Bucharest. It was built in 1858 by the Gaster family, reconstructed in 1903, damaged by the earthquake of 1940 and that of 1987, and was razed that very year. Malbim Synagogue, the most impressive of them all, stood right in the way of what became the Victory of Socialism Boulevard. It was built in 1864 upon the initiative of head rabbi Meir Leibush Wisser, reconstructed in 1912, vandalized by the Iron Guard in 1941, damaged by the 1977 earthquake, then taken down in 1986.

Projects that try to recover the architectural and urban aspects of people’s lives are by necessity anthropological projects. Many of the people displaced by the destruction of their homes never recovered what Anca Tudorancea called their inner map:

“You may ask what happened to the Jews from these areas. This was a period of anti-Semitism, with a lot of emigration, full of challenges. People not only had their homes taken down, but the moment that they applied for emigration, they automatically lost their jobs, and the official approval for the move took several years. The people who wanted to move abroad had to turn in the keys to their homes after renovating them fully. There was a lot of drama here.

The only remnants of the Jewish religious community in Bucharest are Coral Temple, the Grand Synagogue, and the Holy Union Temple, serving the needs of the very small remnant of the old community, now numbering only around 4,000 members.