The beginnings of the hippie movement in Romania

An outlook on how the hippie movement made its way into Romanian culture.

Steliu Lambru, 21.12.2013, 12:06

The hippie of flower power movement was one of the most influential countercultures and non-violent movements of the 20th century, with echoes around the world. It started out in North America, but its universal values quickly spread to the most diverse societies and cultures. The hippie movement was more than a trend in music and fashion, it was a specific reading of the relationship between man and nature.

In communist countries, the hippie movement was long associated with capitalism and frowned upon as a form of degradation of mankind. In Romania, which unlike Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Yugoslavia, had no direct border with the West, the hippie culture had a lower impact. But even an extremely harsh regime as the Romanian communist regime was unable to bar the spreading of such a large-scale phenomenon. The regime manipulated hippie concepts for its own propaganda purposes, in a rather perverse manner. Drug consumption, the sexual revolution and rock music were presented as the damaging effects of capitalism on mankind, but on the other hand the pacifist political component of the hippie movement was advertised by the communist propaganda as a form of dissent of the citizens of capitalist societies against their leaders, in short, as a form of class conflict.

Just like their fellows in other communist countries, Romanian hippies had to face not only the opposition of the regime, but also the reserves of the older generations. Long hair, flared jeans, alcohol drinking, nudism, rock music and a more relaxed outlook on life were the hippie elements taken over by Romanians most extensively. Conversely, the use of drugs, the sexual liberation and, more importantly, the freedom to publicly express anti-war views and to criticize the flaws of the regime remained taboo subjects. Essentially, fashion and music remained the hippie elements that most easily penetrated mainstream culture.

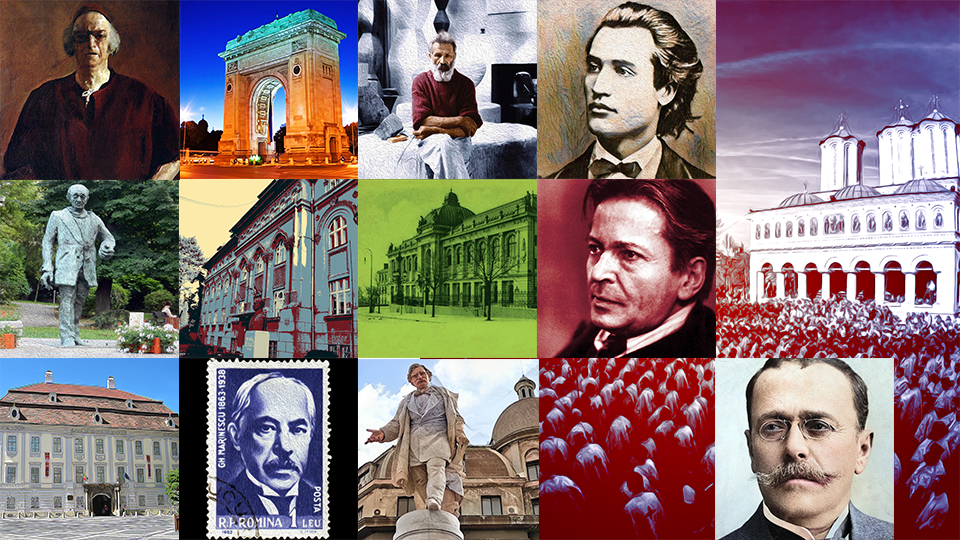

Somehow, the flower patterns and traditional elements in clothing, as well as the songs drawing on folklore converged with the nationalism promoted by the communist regime’s cultural policy. Promoting traditional culture among the young was expected to lead to the cultivation of patriotism, which the regime really needed, and this is why the Romanian-style hippie movement ended up by being tolerated in communist Romania.

Music, in particular, was the field where Romanian hippies were able to dodge censorship. In the mid-60s and throughout the ‘70s, Romania saw the rise of its most valuable rock bands, such as Phoenix, Mondial, Sfinx, Olympic ’64, singer Dorin Liviu Zaharia and actor Florian Pittis. Their models were Bob Dylan, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and the entire generation of the Woodstock 1969, which Romanians had come to know either through Radio Free Europe, or through the tapes and records smuggled into Romania. But although Romanian bands and singers found inspiration in Western songs, their lyrics contained no elements of protest or social criticism. Instead, they were limited to love songs and variations on traditional folk music.

The Romanian hippies’ Woodstock was the village of 2 Mai on the Black Sea coast. Although the parallel may seem extreme, it nevertheless finds echoes in the hearts of all those who spent their summer holidays there in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. Isolated and lacking the investments that would have turned it into a holiday resort, the village of 2 Mai was the meeting place of Romanian hippies, students and intellectuals, who made up a non-conformist and exclusivist, although marginal, micro-universe. The Romanian hippies were unable to build a more visible social identity and act as a source of political action, at a time when being politically active was the central element on the agenda of all hippies around the world. This is why the original anti-system message of the flower power movement remained, in Romania, limited to the world of art, and deprived of one of its most powerful components, namely its rebelliousness, the ideal of a revolution that may change the world.