Sibiu’s Social and Political Life in the 16th century

Of all the towns founded by Saxons in Transylvania starting in the 12th century, Brasov and Sibiu have always stood out.

Christine Leșcu, 08.12.2018, 15:58

Of all the towns founded by Saxons in Transylvania starting in the 12th century, Brasov and Sibiu have always stood out. The first, larger and with a bigger population, was a more dynamic city, trade oriented, more pragmatic, and less conservative. At the same time, Sibiu was always considered the political, administrative, and intellectual center of the Saxons. Its economic ties branched out deep within Central and Western Europe, but also east and south. To a large extent, the wealth in Sibiu was due to trade with the Ottoman Empire, through the towns in Wallachia, such as Campulung-Muscel, Targoviste and Pitesti.

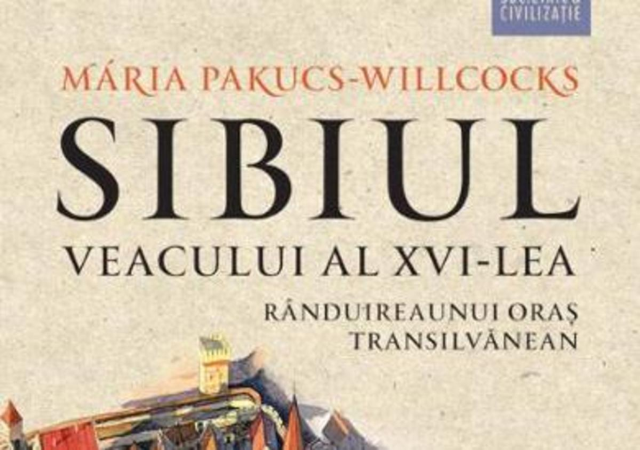

At the same time, Sibiu, as a city inhabited to a large extent by traders and craftsmen, was self-ruled under a system inspired by Central European burghs, but with a lot of local specificity. This specificity, expressed in its social and political arrangements, had its peak maybe in the 16th century. In Sibiu, as in all Saxon cities in Transylvania or German cities in Europe, there was a form of local incipient democracy. The inhabitants of Sibiu annually elected their mayor, their royal judge, and its magistrates. This form of self-rule, along with the legislation that came with it, was in its time referred to in German as gute polizei, good governance. We spoke to Maria Pakucs-Willcocks, who wrote the book called 16th Century Sibiu. The Organization of a Transylvanian City. She told us about how liberal or how advanced for its time this form of autonomy was.

Maria Pakucs-Willcocks: “Sibius leadership, the political elites in Sibiu, try to imprint on the city a certain vision, a policy and ideology symbolized by the phrase gute polizei. It may not have been very popular at first, but it is reflected in the citys statutes, which were of Western European inspiration. There were democratic elections, but, as a rule, the top positions were held by the members of the same few families that formed the entrenched political elite, which could afford financially to deal in politics. They also had the relations that allowed them profit financially from politics. Yes, there were elections, but not just anyone got elected. It was a democracy of the privileged, but they kept good relations with the voters or their representatives. The representatives were a body of 100 men representing the citys craftsmen, and they worked closely with the ruling council. The 100 were also elected annually, and represented the so-called middle class of the city, made up of craftsmen and small traders.”

Other Saxon cities had similar forms of administration, but not exactly like Sibiu. This was in part due to an extraordinary local figure, a statesman still celebrated, since a central square in Sibiu bears his name, Huet Square.

Here is Maria Pakucs-Willcocks: “In Sibiu, we had great personalities such as Albert Huet, a very well educated man for his time, with an exceptional intellectual training. Not every city had an Albert Huet, who was a royal judge in Sibiu between 1577 and 1607. It was he who found this formula, this expression, gute polizei, which only a century later became a part of the usual administrative language. He imposed a way for the Saxon nation of Transylvania to define itself. He navigated very murky waters in domestic and foreign policy. For instance, the reign of Michael the Brave occurred in his lifetime, and he even fought in the Battle of Giurgiu, on Michaels side. He posed as a sort of father of Saxons. He wanted more autonomy for the Saxons, but also the preservation of their political, economic, legal, and administrative privileges. On the long term, these privileges, however, led to inflexibility on the part of the Saxons, a lack of openness to subsequent political developments. Sibiu was rather closed to other nations. Not only were Romanians banned from settling into the city, but any other intruder, intruder meaning anyone who was not a Saxon, a Lutheran, or who was a nobleman. To be a nobleman, for the Saxon bourgeoisie, was unacceptable. This was a big problem for several centuries on end: refusal to take in or grant citizenship to people who did not match the criteria they set.”

Surprisingly, by 1589, Sibiu already had a constitution. Here is Maria Pakucs-Willcocks: “I call it a constitution, but its official name is the City Statutes, which crystallizes the idea of gute polizei, good governance. Also, it set rules and principles for the political and administrative functioning of the city. Consensus was the cornerstone of any community, not just Sibiu. However, in Sibiu it is expressed in certain set formulas: common interest, common peace, the relationship between the governing and the governed, obedience… What does the common good mean in this context, youll ask. It is a contract, a covenant by which the ruled or the governed are obedient, as long as those governing act in everyones interest. As such, the common good would mean the sum of conditions that would allow both sides to live in peace and tranquility.”

With its good governance, its traditions, and even its 16th century constitution, Sibiu had a great contribution to the diversity of cultures and civilization that now form Romania, which this year celebrates 100 years of existence.