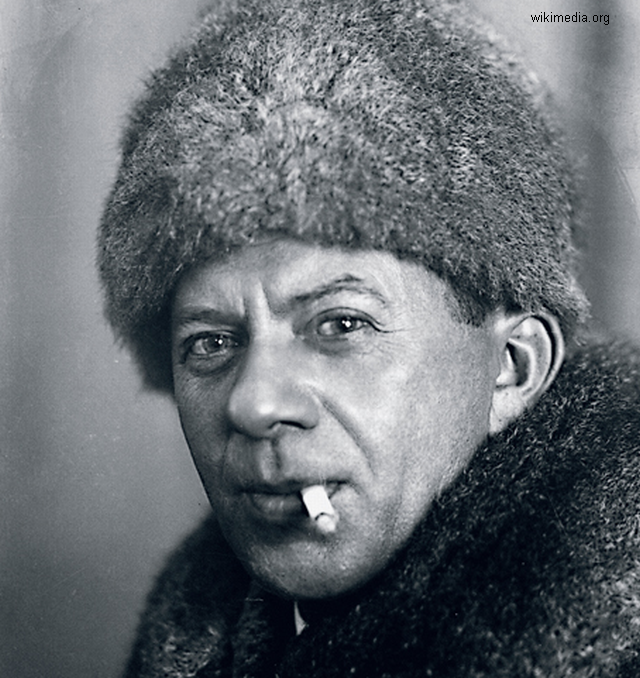

Photographer Iosif Berman

After the Great War Iosif Berman was Romanias first professional reporter.

Christine Leșcu, 01.02.2014, 12:00

Born on January 17, 1892 into a Jewish family in the town of Burdujeni, northern Romania, Iosif’s love affair with photography started very early. Back in the time of WWI, he accompanied Romanian troops right up to the frontline as a war correspondent. After the war he settled in Bucharest where he began the most fruitful cooperation of his career, with journalist Filip Brunea-Fox, a man his peers dubbed the ‘Prince of the Reporting’. Between 1924 and 1938 the two worked for two newspapers, ‘Adevarul’ (the Truth in Romanian) and ‘Dimineata’ (The Morning Post). Researcher Anca Aurelia Ciuciu with the Centre for the Studies of the Jewish People in Romania, has more on Bergman’s career.

Anca Aurelia Ciuciu: “On the one hand, Berman presented the upper class, including the royal family, as he was the latter’s official photographer, but also wrote about the life of the needy, covering aspects of life in the slums of Bucharest. He was a photographer whose stories could be easily understood without descriptive texts, because his photos were extremely descriptive and for a good reason. He used to spend weeks doing research before taking a snapshot and talked to people beforehand. A photo of someone you know and understand is worth a thousand words. Even the way he approached his subjects is different. Most of the time, the people in his photos are smiling, and that actually gave a headache to the communist propaganda machine, which was trying to use some snapshots he took while doing monographic campaigns around the country together with sociologist Dimitrie Gusti. They were pictures of happy people and were completely useless to the communists striving hard to prove how unhappy people were before coming to power”.

The glee, humanity and tenderness of poor neighborhoods were the highlights of photos taken by Iosif Berman as illustration to articles written by Brunea-Fox. He worked his photos as any artist would.

Anca-Aurelia Ciuciu: “He did not just carry out an analysis of the protagonist, a lot of aesthetic prep work was also involved. He was keen on shadows and shapes, he was known as ‘the cloud chaser’. He was passionate about photography and the latest trends in photographic depiction. He was a perfectionist, he spent a lot of time in the dark room to perfect details to the last. From his family we found out his work days were very long.”

His talent and perfectionism earned him collaborations with foreign publications. Berman was a New York Times correspondent, he worked with the Associated Press, and contributed photos to National Geographic. They were recently discovered and reprinted by the Romanian edition of National Geographic. In the early 1940s he sent abroad photos covering domestic politics, at that time chiefly the rise of the fascist Iron Guard.

Anca Ciuciu: “In the 1940s he tried to work for foreign press agencies and sent them photos which were not published in Romania. This was before the ban slapped on him because he was Jewish. He was not very successful, because he could not work after 1940. He was barred from owning a camera, because it was considered a propaganda tool, and this is why he fell ill. Berman died shortly after this ban.”

A victim of the racist legislation of the era, the photographer fell ill. His kidney ailment killed him in 1941, in September. Right now Iosif Berman’s photography archive is spread all over the world, and his works are hosted by a large number of museums and private collections. His archive of negatives is no longer in mint condition. Many of them shattered during the great earthquake of 1977, and some of them are owned by the Romanian Peasant Museum, namely those photos taken during campaigns undertaken alongside Dimitrie Gusti.