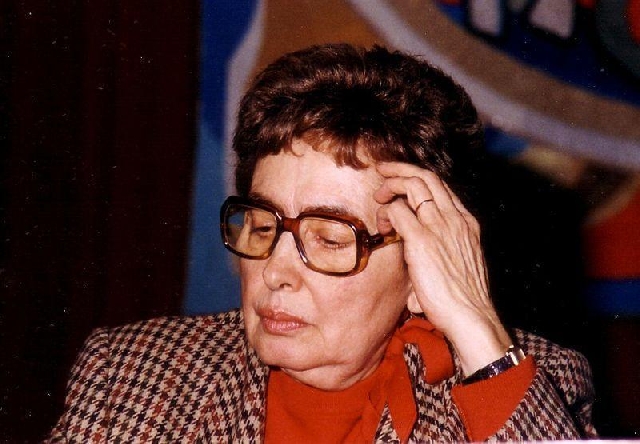

Monica Lovinescu

Monica Lovinescu was born on November 9, 1923 and passed away on April 20, 2008 In Paris. Jointly with her husband Virgil Ierunca, Monica Lovinescu was one of the icons of the Romanian anti-communist exile, sine she mainly came to be known for the lucidity and acumen she showed in her efforts to debunk the fat lies of the communist propaganda.

România Internațional, 08.12.2013, 14:27

Monica Lovinescu was born on November 9, 1923 and passed away on April 20, 2008 In Paris. Jointly with her husband Virgil Ierunca, Monica Lovinescu was one of the icons of the Romanian anti-communist exile, sine she mainly came to be known for the lucidity and acumen she showed in her efforts to debunk the fat lies of the communist propaganda.

Yet Monica Lovinescu will also be remembered because of her very special life. She was the daughter of literary critic Eugen Lovinescu, who in the early through the mid-1930s was a staunch supporter of modernism in Romanian literature. Her mother was the French teacher Ecaterina Balacioiu Lovinescu. Monica proved she had literary talent at a very early age, as when she was a child she got several of her texts published.

Yet the early days of her literary attempts would subsequently be denied, since right after the war Monica Lovinescu began to write play reviews. In September 1947, a little bit before King Mihai’s abdication and the indefeasible instatement of the communist regime in Romania, Monica Lovinescu left for Paris on a scholarship offered by France, and never returned.

As an exile, she continued her columnist activity, and since 1962 she started to collaborate with Radio Free Europe, where she had two bi-weekly radio shows: “Romanian Culture Today” and “Theses and Antitheses in Paris”.

Right after she settled in Paris and as soon as she began targeting criticism at the communist regime in Bucharest, the Romanian authorities began to persecute her mother. 71-year old Ecateriana Balacioiu-Lovinescu was sentenced to prison and deprived of her supplies of prescribed medication, as a blackmail attempt for her daughter to return to the country. Monica Lovinescu’s mother died in prison in 1960, and the communist regime in Bucharest never ceased to stalk her in France.

In 1977 in a coup the Romanian Securitate staged against her, Monica Lovinescu was severely beaten and was admitted to hospital. Despite all that, she was unwavering in her anti-communist stance. Actually there was not a single period of time in her life when Monica Lovinescu might have taken sides with the communist doctrine, and that quite unlike other intellectuals who, having bowed to the communist doctrine, later on regretted all the commitments they had made.

Speaking now is literary critic and novelist Angelo Mitchevici, who will be giving us an outline of Monica Lovinescu’s biography: ”Here’s what’s most remarkable about Monica Lovinescu: the lucidity very few intellectuals had. I have no explanation for that kind of lucidity other than her moral fiber. Monica Lovinescu did have a reasonably strong moral fiber. Using her own words when she used to speak about Arthur Koestler, we could say that before being the author of a work which was valuable in itself, Monica Lovinescu authored a kind of life that had never been dented by any fall, by any blemish, by any take-back for she might have previously said.. That kind if life was nearly perfect, limited as the accomplishment of perfection may be in this world. That was something she used to say about Arthur Koestler, but which equally applied to her as well: the fact that she turned her life into a risk she would continually take. I believe Monica Lovinescu can be an example of life turned into a risk she’d never ceased to take. We all know the Securitate was extremely keen on dealing with those who were part of [Radio] Free Europe’s small circle. There were assassination attempts, and some of them were even successful. Monica Lovinescu got beaten, but she miraculously escaped what could have been a murder. So all in all, I can say that in a nutshell her existence can be captured in the words moral fiber. And moral fiber, Monica Lovinescu had galore from the very beginning.”

In a rare recording of Radio Romania’s Golden Tape Archives, here is what Monica Lovinescu said, capturing the moment when she took full responsibility for her destiny of a committed intellectual, as well as the reason why she made that choice.

Monica Lovinescu: ”There were other temptations for me as well: stage directing, literature. It was not a decision to be taken under the spur of the moment, but the main reason for that was the feeling I got that from here, you could speak up. And speaking, I had to redeem the silence of those back home, who back there were stifled into silence. I somehow had the feeling I had to pay for that freedom which, it seemed to me, was being offered conditionally, in return for something else. I believe I sacrificed the writer, but with no great remonstrance, at that. I kind of sensed I had to do it, given the fact that many intellectuals died in prison and that my own mother died in prison, and the choice writers had to make was again between prison and prostitution. Under the circumstances, it was more useful for me to do what I was doing, rather than writing yet another novel.”

Before she died, Monica Lovinescu donated her home in Paris to the Romanian state, while her personal archive, as well as Virgil Ierunca’s archive were donated to the Humanitas Aqua Forte Foundation, which is the foundation body her father Eugen Lovinescu’s apartment.