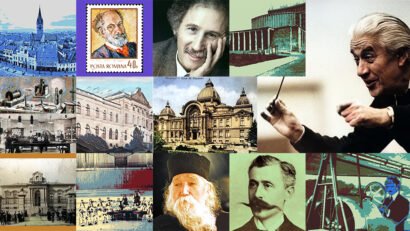

Filipescu Estate

Towards the end of the 19th century, Bucharest was booming and the need for urban planning was growing

Christine Leșcu, 20.10.2018, 13:47

Taking

the northern exit from Bucharest, following one of the oldest and most

important boulevards, Victory Road, overpassing the current headquarters of the

Romanian Government, one arrives at the junction of another two large main

roadways: Kiseleff Road and the Aviators Boulevard. In the 19th

century, the two merged into one of the capital city’s peripheries, known as

The Road. It was an ideal place for strolling, going for a picnic, a place

where the hustle and bustle of the city room left room for large stretches of

gardens, orchards and vineyards. Towards the end of the 19th

century, when Bucharest was booming and the need for urban planning was growing,

the Road itself started to change, being torn in two: one half stretched

alongside Kiseleff Road, while the other had several names, one of them being

Jianu Road, today’s Aviatorilor Boulevard.

Oana Marinache, an art historian,

told us more:

A major step towards the urban configuration of the city was the layout of the

former Coltea Boulevard, the segment linking Romana Square to Victory Square,

today’s Lascar Catargiu Boulevard. This boulevard was instated during the

mandate of Mayor Nicolae Filipescu, at the end of the 19th century

and in early 20th century. Starting 1902 the authorities were

already considering widening Jianu Road and creating a system of urban

regulations, after these vast estates were expropriated, with a view to

clearing land for the build-up of residential areas.

Without any

direct connection to mayor Nicolae Filipescu, Alexandru Filipescu, the nephew

of an important and rich boyar nicknamed ‘the Fox’ would also contribute to the

process of streamlining the Jianu Road. Here is Oana Marinache again:

He was

dubbed the ‘Fox’ as he was very cunning and good at negotiating his position at

the court irrespective of the political changes of the time; he used to be so

good at adjusting to the political context. He remained unmarried but had an

illegitimate son whom he eventually acknowledged and named Ioan Filipescu. Ioan

later married Eliza Bibescu, daughter of the Romanian ruler Bibescu, and had a

son, Alexandru Filipescu, the one who was going to make the difference in the

process of streamlining the aforementioned road. In 1912 he got the idea of

dividing the estate he had inherited from his grandfather. In a relatively

short period of time, this boyar who had the spirit of a real estate developer

managed to sell about 120 plots of land each ranging between 500 and 1,000

square meters. This initiative developed until WWI and Alexandru Filipescu died

in 1916. He paid to fit his estate with all the needed utilities. He also gave

Bucharest two parks, two green areas in order to contribute to the idea of a

garden-city. He wasn’t only into property speculation but was also interested

in improving and developing the area. He kept for himself a big plot of land

towards the Jianu Road where he built himself a villa after architect Roger

Bolomey’s plans. He also laid out the

alleys behind his estate after a French pattern, bordered by various species of

trees. He named these alleys after his ancestors and that’s why one of them is

called Alexandru Alley.

Prince Alexandru

Filipescu’s villa, that can still be seen today on Aviatorilor Boulevard, is

one of Bucharest’s architectural jewels, according to art historian Oana

Marinache:

The

blueprints for the villa are signed by Roger Bolomey, a Swiss-born architect

from the town of Piatra Neamt, where he

worked as an architect and where signed the blueprints for some very special

villas. Coming from the Moldavian area, the Neo-Romanian style that he adopted

was obviously influenced by elements specific of that area, such as apparent

brick and the turret foyers specific to the monasteries in Bucovina.

Little by

little, one of the city’s most beautiful residential areas developed, after the

parceling out of the Filipescu estate. Owners bought their plots of land between 1912

and 1913 but the construction of villas continued until the inter-war period. Owners

were generally well-off people, such as bankers, politicians, boyars,

industrialists and also artists. The general architectural style, although not

rigidly regulated, was mostly Neo-Romanian, which became popular especially

after the Union of 1918. An example in this respect is the villa that hosts the

main office of the Romanian Cultural Institute.

Oana Marinache: Vasile

Mortun is the first owner and commissioner of the villa located on Alexandru

Alley at no 38, built by architect Petre Antonescu. In the inter-war period the

villa was bought by industrialist Nicolae Malaxa who extended it after the

plans of architect Richard Bordenache. Also, the area started to be inhabited

by painters and artists who wanted to live close to each other. Given that the

architectural style of Bucharest was not strictly regulated, a wide range of

new projects signed by important Romanian and foreign architects emerged.

In spite of the

destruction and change specific to the communist regime, the area has

maintained its elegant aspect.