110 years since the birth of Emil Cioran

Emil Cioran was one of the greatest philosophers of despair in the European post-war culture

România Internațional, 15.05.2021, 12:49

Born on April 8th, 110 years ago, in Rasinari, Sibiu County, Emil Cioran would become one of the greatest philosophers of despair in the European post-war culture and one of the biggest stylists of modern French language. He started as a writer in the 1930s in Romania, with extremely unconventional texts, as member of the 1927 generation, whose undeclared leader was Mircea Eliade. In its turn, that generation of young intellectuals proved original and controversial, both due to its members’ special talents, and also due to some Legionnaire or far-right sympathies expressed by some of them, Cioran included.

In the 1940s, thanks to a scholarship granted by the French state, Cioran went to Paris where from he would never return back home. It was there that he wrote, in French only, the books that made him famous in the West. After 1990s, he was discovered by the Romanian intellectuals who started publishing his books in Bucharest and taking him interviews, on the rare occasions when he accepted. One such interview was made by the director of the Humanitas Publishing House, Gabriel Liiceanu, who recalls Emil Cioran as he was at the age of 79:

He was no longer a volcano, but he had preserved all the traits that characterised his personality. He was funny, his stylistics was unbelievable, and he was a great actor, a poser actually, just like Eugen Ionesco. Back then, in 1990, I had the revelation of the free man looking into another free man’s eyes who could act the words, by intervening in the discussion and accompanying words with gestures and facial expressions.

The first book written by Emil Cioran in French was published in 1949 by Gallimard: Precis de decomposition (Treaty on Decay). There followed, until 1987, another nine, published by the same publishers in Paris. Except for the Rivarol Award, which he got in 1950 for French debut, Cioran refused all the awards and prizes he won later, such as Sainte-Beuve, Combat, Nimier.

Here is Gabriel Liiceanu again about the existential drive behind Cioran’s writings:

He truly believed and lived in his own way this drama of being thrown into the game of life, or stage, without anybody asking whether he had wanted it or not, just like the rest of us. At the age of 18-20, Cioran went through a terrible existential crisis. Somebody pushed me into life. I did not want it, it was not my choice, I don’t like where I am. So, what can be done? And his answer was: All I can do is relive myself from these negative emotions by slandering God, myself and everybody else. Everything is just an abomination, starting with the human race. In the interview he says at one point that my work emerged out of therapeutic, medical reasons. I wrote the same book, over and over again, based on the same obsession, because I noticed that was a form of liberation for me. So, in fact, I wrote out of necessity. Literature and philosophy were just a pretext, what mattered was writing as therapy.

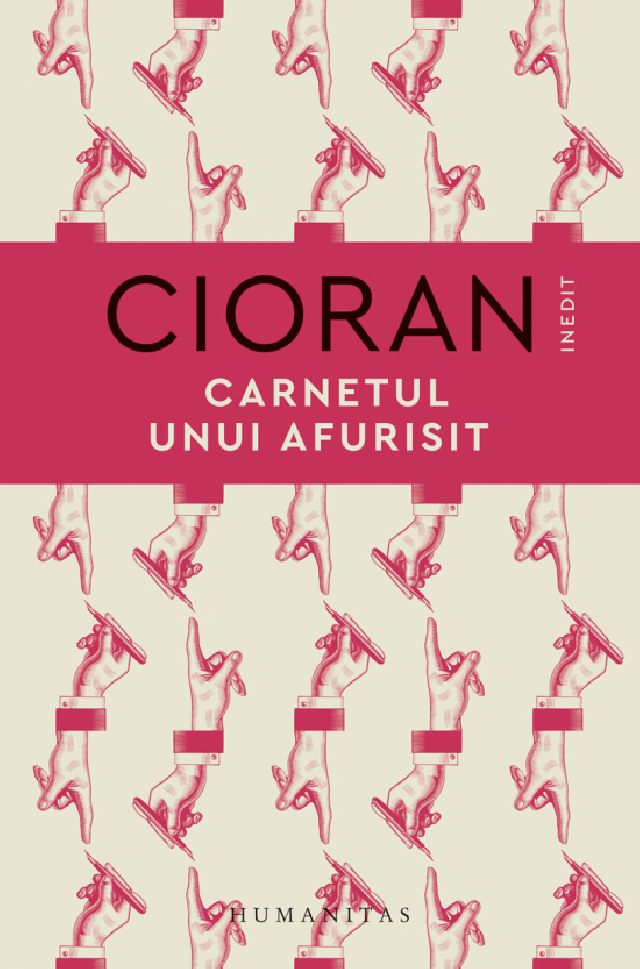

Recently, Humanitas has published another therapeutic text signed by Emil Cioran, a special book, the last one written in French, and titled The Diary of a Damned, edited by Constantin Zaharia. Writer and translator Vlad Zografi tells us more about the adventure of compiling this book out of texts he discovered at the Doucet library in Paris, which owns a large part of the Cioran archives:

It’s hard to date them, but I think they’re from the 1941-1946 period. Some hand-written papers were found, which Constantin Zaharia transcribed. The text had no title and the ending is actually a phrase extracted from the content. What shocked me about it? It’s probably one of the very last texts that Cioran wrote in Romanian, before passing to French. It was a turning point then, when he was trying to translate Mallarme and he understood he had to give up Romanian. There are many words here that sound priestly, because, maybe, they’re from the time when Cioran did not have many interlocutors in Paris, before the emigration wave of 1946-1947. Back then he would read the Bible and religious texts which he would find at the Romanian church in Paris. And I would like to give you an example, because I didn’t read anything like that in the first texts written in Romanian by Cioran. He says: God, you have given me nothing. Not even I belong to myself. Time is senseless, like the smile of a blind man, and I spend my time chanting thoughts without end, which are of no concern to anybody. Could it all be, including you, just a crazy twist of a fallen mind? Am I, unwitting and damned, twirling between fear and callousness?

Could these words be the signal of another identity crisis experienced by Emil Cioran back then, one that had him give up Romanian language? One can possibly find the answer in this unique book published in celebration of 110 years since the birth of the great Romanian thinker. (MI)